Giles Auty considers the purchase of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles by the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra in 1973 and what such an acquisition signifies.

A few months back, a rash of articles appeared in the press which commemorated the dismissal of the Whitlam government thirty years ago and commented on the continuing sense of grievance felt by his supporters. At the time, I wondered how much more could usefully be written on the subject.

By contrast, an event of almost equal notoriety if not importance had taken place in Australia some two years before the dismissal which has never been explored or explained satisfactorily. I refer to the purchase of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles in August 1973 by what was then called the Australian National Gallery.

By contrast, an event of almost equal notoriety if not importance had taken place in Australia some two years before the dismissal which has never been explored or explained satisfactorily. I refer to the purchase of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles in August 1973 by what was then called the Australian National Gallery.

In the ten years that I have lived in Australia so far, I have often heard the view expressed – in leftist circles especially – that the buying of Blue Poles provided a catalyst for Australia’s cultural coming-of-age. According to this received wisdom an increasingly confident nation – inspired by the leadership of Gough Whitlam – not only bought itself a wonderful work of art but an outstanding bargain at the same time.

Many might feel disappointed if neither of these facts proved true. Indeed, until the significance or otherwise of the painting itself and the circumstances surrounding its purchase are dragged belatedly into sharper focus, Blue Poles may yet prove to have been a hindrance to the attainment of national cultural maturity rather than the reverse.

Perhaps the first part of the myth to dispel is that Australia plucked an outstanding bargain from under the noses of older and more established museums overseas. What Australia really seems to have done is buy itself a monument to a formerly fashionable but highly questionable notion of artistic progress. Indeed, no sooner had the painting arrived here than this notion found itself the subject of increasingly vocal international critical attack.

To put it another way, Blue Poles could be said to represent a kind of last hurrah for an outdated and weirdly monolinear conception of the evolution of art. Indeed, by the time Pollock had painted it, he and his friends were openly declaring that painting had “nowhere left to go” and could be followed henceforward only by “performance” art.

I will return to this issue of evolution a little later. For the present, I should begin perhaps with a subject which seems to grab public attention much more readily than the vested and supposedly insoluble issue of artistic merit. In short, how much exactly is the damned thing worth?

Guesses – and that is all any of them are – about the current market value of Blue Poles range from US$20 million to a highly improbable US$100 million but the accuracy or otherwise of these guesses cannot, of course, ever be tested unless the work is offered for sale. At the time of its purchase in 1973, the price paid – US$2 million – represented only A$1.3 million.

So if we take US$20 million as a realistic starting point for the current market value of Blue Poles, it becomes apparent that it has increased in value by at least ten times during the thirty-three years Australia has owned it. However, this by no means represents the greatest recorded acceleration in its market value. In 1953, three years before Jackson Pollock’s untimely demise, the American dealer Sidney Janis sold Blue Poles to Dr Fred Olsen for $6,000. But shortly after Pollock managed to kill himself and one other by driving when unfit to do so, Ben Heller – another American dealer – was prepared to pay $32,000 for the work.

In art, nothing can compare with death as a means of jacking up market prices. But if we take 1953 as our starting point, the next twenty years, culminating with the purchase of Blue Poles for the Australian nation, saw its price rise by a giddy 166 times. Even in the sixteen years after Heller bought it its market price rose thirty times. In other words, the last thirty-three years have witnessed a sharp slowing down of the rate of increase of its supposed market worth.

I am tempted to suggest that if the Australian National Gallery had forked out US$2 million in 1973 on purchasing housing in the Canberra area – in preference to Blue Poles – the gross return on its investment might well have been greater. Yet the notion that Australia made a uniquely inspired purchase in monetary terms is only part of a greater myth which continues to surround Blue Poles. Surely no less to the point is whether Blue Poles really is an outstanding work of art.

Where might we turn for informed opinions? What about starting with the artist himself? In Florence Rubenfeld’s biography of the American art critic Clement Greenberg (Clement Greenberg: A Life, 1997) we have Greenberg’s word that Pollock himself considered Blue Poles “a failure”. But Greenberg, who was probably Pollock’s most consistent supporter, was even more dismissive, declaring unequivocally that Blue Poles was “an absolute failure and a ridiculous thing to buy”. This comment is reported in Patricia Anderson’s biography of the late Elwyn Lynn, Elwyn Lynn’s Art World (2001). Lynn was my predecessor as art critic for the Australian.

But Blue Poles did not lack professional supporters at the time of its purchase. Indeed yet another former art critic for the Australian, whose tenure there (1972–84) comfortably exceeded my own, certainly did not share any of Pollock’s or Greenberg’s misgivings about Blue Poles. Writing in the Weekend Australian of August 25th, 1973, Sandra McGrath evidently preferred the enthusiasm shown by New York-based Australian art dealer Max Hutchinson – who personally brokered the sale of Blue Poles to the Australian National Gallery – to the reservations expressed by Pollock himself and Greenberg.

Dipping deep into her handbag of superlatives, McGrath proclaimed that “the purchase of Blue Poles is the most momentous event in the cultural history of Australia” and “Jackson Pollock is … the artist whose work made it impossible for painting ever to look quite the same again”. Max Hutchinson proposed that “Blue Poles, along with Picasso’s Guernica and Monet’s waterlilies, is one of the five or six great works of art painted since the Renaissance”. Perhaps embarrassed by the enormity of her colleague’s claim, McGrath nevertheless chipped in with “it is certainly one of the five or six great paintings of the twentieth century”.

These are certainly extravagant claims which cannot begin to be taken seriously unless both Hutchinson and McGrath were known to have an unusually encyclopaedic grasp of art history. This would certainly be unusual in the case of a dealer. If I had been working here at the time, I would have been keen indeed to ask Mr Hutchinson which particular artists he would have picked to fill his last two or three available slots as producers of “the five or six great works of art painted since the Renaissance”.

The task of choosing between the lifetime productions of the likes of Caravaggio, Velazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Veronese, Tiepolo, Goya, van Gogh, Cézanne, Manet, Matisse and Picasso – to name just a handy dozen – would certainly be a daunting one even for someone thoroughly familiar with the greatest works of all twelve.

An altogether more sensible question might be whether Blue Poles could be said to rank even in the top five or six of Pollock’s own productions. On the basis of the definitive exhibition of Pollock’s art I saw when it was staged by the Tate Gallery in London in 1999, I would argue that it could not. I imagine that a number of other professional commentators who are similarly familiar with Pollock’s work would agree with me.

Yet evidently most of those who gawp daily at Blue Poles on the walls of what is now called the National Gallery of Australia cannot be expected to share this degree of familiarity with Pollock’s work. Indeed, few members of the public who have seen Blue Poles at that venue will ever come face to face with any other work by Pollock. Unavoidably, therefore, most members of the public will be largely reliant on hearsay and the fact that the work is seemingly legitimised by where it hangs in forming any conclusion at all about its merits.

In the event, the fact that anything hangs on the walls of the National Gallery of Australia or on those of the principal galleries of Australia’s states should not be looked on as any guarantee of anything, since all have proved pretty fallible at times in their buying policies.

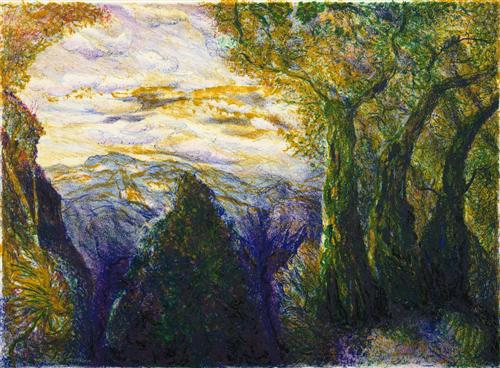

As recently as 1999, for instance, the National Gallery of Australia made a colossal error of judgment not just by buying David Hockney’s huge (744 centimetre) and weakly conceived A Bigger Grand Canyon but by paying a grossly inflated price for it (over A$4 million). No less to the point, that same institution only months earlier had turned down the chance to acquire a truly magnificent giant landscape (810 centimetre) by a home-bred artist. This was William Robinson’s Creation Series: The Ancient Trees, which also carried a rather more realistic price tag of A$250,000. (For more about William Robinson see http://www.ogh.qut.edu.au/wrgallery/past/realms.jsp.)

As recently as 1999, for instance, the National Gallery of Australia made a colossal error of judgment not just by buying David Hockney’s huge (744 centimetre) and weakly conceived A Bigger Grand Canyon but by paying a grossly inflated price for it (over A$4 million). No less to the point, that same institution only months earlier had turned down the chance to acquire a truly magnificent giant landscape (810 centimetre) by a home-bred artist. This was William Robinson’s Creation Series: The Ancient Trees, which also carried a rather more realistic price tag of A$250,000. (For more about William Robinson see http://www.ogh.qut.edu.au/wrgallery/past/realms.jsp.)

What I am suggesting with regret is that the standards of judgment shown by Australia’s national and principal state galleries are frequently inept. Generally this is because judgment is skewed by predilections for fashion and temporary fame and because curators and directors have managed to persuade themselves somehow that novelty must be a virtue in itself.

The reason why the latter trait has become so firmly entrenched deserves urgent investigation. My own explanation centres on the insidious role played by what I call “the rhetoric of radicalism” in creating current and recent artistic climates.

Rhetoric, as we know, describes language designed to persuade or impress. Its natural habitat is politics and advertising but, in both of those fields, long acquaintance has led intelligent minds to recognise its nature and dilute its effectiveness. Regrettably, the full toxicity of such language still takes effect in areas where the ubiquity of its use remains unrecognised. In no area is this truer than in the visual arts.

The twentieth century, which was dominated by modernism in the visual arts, saw the rise and fall of about forty readily identifiable and supposedly significant art movements in the Western world alone. Can there really have been an art movement for every two and a half years of an entire century? No other hundred-year period can even begin to compare with the twentieth century in this regard. And who today, other than specialist art historians, can give an accurate account of what Orphism, say, or Rayonism were? Yet in their heydays many people believed wholeheartedly in the significance of both movements.

So what was it precisely that first led to the obsession with novelty in art which has never gone away?

Though few seem to have made a serious effort to define what does or does not constitute modernism in any of the arts, its most evident and unifying characteristic clearly has to be rejection of past ideas and practices. Indeed, if such rejection is absent we are not really talking about modernism at all. For a modernist label to apply, the break with past practice has to be total.

Thus when, at the conclusion of the First World War, Picasso – whom many might consider the epitome of the modern artist – embarked on a series of neo-classical works as an oblique tribute to Renoir, his erstwhile collaborator in Cubism, Georges Braque, was quick to accuse him of “betraying modernism”.

From the outset, modernism in art, which liked to portray itself as a liberating force, had its own rigid set of prohibitions. In short, modernism’s paid-up followers were free to do anything they chose with the exception of maintaining any overt links with a pre-modern past.

Two linked factors underlay the seemingly inexorable elevation of formal radicalism in art to a position of effective dominance. The more obvious of the two was the conscious or subconscious but ultimately unjustified connection many people made naively between the evident and very real advances which were taking place in other, unrelated disciplines – in medicine, say, or powered flight – with what was happening in art roughly at the same time. Yet the less obvious of the two factors was certainly no less influential. This was the way radical practices in the arts – taking their cue from technology – first attracted to themselves and then virtually annexed a wholly favourable rhetorical language.

In short, to situate oneself on the side of what many claimed was “inevitable” progress – or advance, development, evolution, breakthrough or “fearless” experimentation – was to place oneself, rhetorically at least, fairly and squarely in the camp of the angels. By seizing for its own purposes the positive, propagandist language associated with claimed progress in other fields, modernism in art ensured for itself for the foreseeable future a very unlevel playing field wherein even the most acute and perceptive criticism could be dismissed airily as conservative, reactionary or – worst of all perhaps – as being “opposed to progress”.

Carried away by its borrowed rhetoric, the elementary truth that modernism chose to ignore here is that there are two equally vital traditions and sources of influence in art – as well as in all other aspects of human behaviour – the radical and the continuous. Perhaps the most damaging legacy of modernism has thus been the part radicalist rhetoric has played in obscuring so obvious a truth from so many for so long. To cite merely one obvious example, it would be impossible to be wholly modernistic or radical in one’s ideas and at the same time be a committed Christian. Christianity antedates modernism by a little matter of 1900 years and thus is part of a continuous tradition.

Perhaps the most apt parallel one might find for modernism is Marxism, since both, in a sense, attempted to rewrite history by subverting and stamping out existing ideas and practices. Although both ideologies had their roots in nineteenth-century thinking, neither came to full flower before the first and second decades of the twentieth century. Both also held out explicit or implicit promises of the future triumphs which would attend their causes: the final victory of the proletariat and a kind of artistic apotheosis which would mark the culmination of the oddly one-track model of artistic evolution which modernists favoured.

There is little doubt that it was this kind of crowning achievement which the modernist faithful believed they discerned in the subconsciously-driven “action” paintings of Jackson Pollock. It is this apotheosis, rather than a fairly incoherent mass of paint which attempts to redeem itself through the use of unusual vertical bars, which all of us are supposed to see when gazing at Blue Poles.

Yet I doubt whether even one in a hundred visitors to the National Gallery of Australia has the least inkling of this. Indeed, I am reminded of a comment made when Blue Poles was first revealed to an expectant Australian public: “I had rather hoped it would be bluer.”

When Australia managed to “beat down” Ben Heller in 1973 from an asking price of US$3 million to a “bargain” price of $2 million, both figures were plucked strictly from fantasy-land. As expatriate Australian art critic Robert Hughes remarked somewhat sourly when delivering the Harold Rosenberg Lecture at the University of Chicago in 1984: “My fellow countrymen were rather proud of beating Ben Heller’s creative asking price down from $3 million. Nobody had even thought of asking so much for a Pollock; but of course the market gratefully rallied behind this heroic example and every Pollock in the world quintupled in price overnight, thus enabling the National Gallery of Australia to announce that Blue Poles was really cheap …”

Clearly the National Gallery of Australia has a vested interest in maintaining its self-created myth of prescience and inspired financial acumen in the matter of Blue Poles. But surely the time has come now to put the merits or otherwise of the painting itself into some more credible perspective.

What is basically wrong with the Pollock is also what is wrong with the arguments for modernism themselves: to wit, to suggest that the narrative of Western art should be read as a kind of art-historical relay race which culminates in the death of painting simply because there are no more apparent avenues of novelty left to explore is both spurious and infantile. If a map of modernism is largely a chart of cul-de-sacs then the time has come to admit this.

Jackson Pollock, despite his long history of alcoholism and failed attempts at remedial therapy, had a much more cogent appreciation of the dangers of artistic dead ends than that shown subsequently by his apologists. Blue Poles belongs to a period of his work of which the artist himself had grown weary. In fact, the type of “all-over” abstract painting to which Blue Poles broadly belongs occupied only a relatively brief interlude even within the parameters of Pollock’s truncated career. Ample evidence exists that if he had lived longer he would have worked very differently. Before and after Blue Poles and the short era of other poured and dripped paintings, Pollock’s work featured a variety of clearly recognisable imagery drawn – or perhaps wrestled – from his troubled subconscious.

Pollock taught himself to pour and drip paint with a singular, highly developed and concentrated skill and in so doing successfully sidestepped the relative clumsiness of his more directly manual mark-making. As Robert Hughes remarked in 1982, Pollock “was by no means a natural draftsman and his best paintings of the early forties … are set down with earnestness by no graphic facility”.

No one with any knowledge of the subject would deny that there is a validity of a kind in abstract painting and that attempts to resolve wholly abstract works seem to bring into play processes of “pure” intuition which can be extraordinarily exhilarating for the artist involved. At times the artist’s hand seems to be a direct conduit for unknown forces; out of the blue, the receptive artist suddenly feels a “need” for a small, bright yellow, triangular shape near the top right hand corner of his canvas …

But the question remains as to whether such a process can genuinely be said to mark the culmination of all the centuries of much more deliberate-seeming and humanistically relevant painting which had gone before. Then, too, there is the matter of the belief that modernists hold that the history of art should be read largely in the light of the supposed contributions earlier artists made to a process which culminated in “total” abstraction. Major artists as various as Whistler and Turner are regularly recruited posthumously – and thus involuntarily – to this cause.

As someone who sees the history of art as seamless, I would argue strenuously against both of these propositions. Let us imagine for a moment that I am stood simultaneously in front of Blue Poles, Titian’s The Flaying of Marsyas (1570–76), The Surrender of Breda (1634-35) by Velazquez, and Goya’s Fantastic Vision (1819–23) – to cite merely three points of comparison from thousands available – could I put my hand on my heart and say I see Pollock’s painting as an “advance” on the other three? The simple answer is I could not, and suspect that many others who are familiar with all four works would agree with me.

The big problem here from the point of view of the Australian public is that any such exercise becomes harder to imagine because of the relative inaccessibility of major works by earlier generations of European artists. Two of the four paintings I have cited can normally be seen only in Madrid while a third, by Titian, is more inaccessible still.

It seems to me the whole notion of modernism and modernistic “progress” can survive only in a kind of vacuum where all evidence of the staggering artistic feats of the past is deliberately ignored, or misunderstood, or expunged from memory, or – as is the tragic case of Australia – is largely unavailable for assessment. To believe Blue Poles is one of “the five or six great works of art painted since the Renaissance” – as Max Hutchinson averred – can stem only from infantile delusion or utter unfamiliarity with the world’s great collections of art.

As I suggested earlier, ignorant idolisation of Blue Poles locks Australia into a situation of cultural backwardness which only the conscientious teaching of art history and compulsory visits to the world’s great collections of art could even begin to address.

The basic reason why I do not believe Blue Poles represents any kind of qualitative advance on the three paintings I chose above, more or less at random, from three earlier centuries, lies beyond anything in its incoherence and self-absorption. I cannot imagine for a moment that Titian, Velazquez and Goya would ever have believed that a day would come when simply dribbling or pouring paint onto a support might be looked on as a worthwhile end in itself.

The very late Titian I have chosen, painted between the artist’s eighty-fifth year and his death at ninety-one, is extraordinarily expressive and free yet also brilliantly considered in the way it organises seven figures and a dog in portraying a terrifying subject from pagan mythology. The degree of imagination shown is stupendous, as it is in the relatively early Velazquez I have cited, painted when the artist was just thirty-five.

The huge Velazquez, which chronicles an actual historical event, is no less brilliant in its organisation of multiple figures, landscape and complex sky. The clarity, painterly intelligence and graphic skill shown are similarly staggering. How can an incoherent mass of marks by Pollock, covering roughly the same surface area as the Velazquez, possibly be said to compare with it?

Regress, rather than progress, leaps to mind here, yet the great claim made by Pollock’s apologists is that he “went beyond” Velazquez’s fellow countrymen Miro and Picasso. But was the direction in which Pollock supposedly “went further” ever remotely worth travelling? In my experience this is just the sort of question which modernists avoid.

From quite an early stage Pollock’s art was rooted in the subconscious yet contributes nothing in particular to our knowledge of the subject. Contrast this with the intriguing, metaphysical nature of Goya’s Fantastic Vision, which features two flying figures – or witches – who are being shot at by earthbound soldiers. One of the flying figures gestures towards a citadel on a hill. Although fantastic, the scene is hauntingly credible, like a miraculously direct delineation of a meaningful dream.

I do not wish to single out Australia as displaying anything nationally unique in the way of uninformed artistic attitudes. Without intelligent programs of education, confidently pursued, ignorant artistic attitudes are more than likely to be internationally widespread.

As some small evidence of this, the following conversation took place recently in Britain between David Lee, an art historian and admirably forthright art critic, and someone who sounds like a youngish if invincibly opinionated artist. The conversation was reported in the July-August 2005 edition of The Jackdaw, a newsletter for the visual arts edited by Lee: “During a recent meeting I received a damn good ticking off from an artist. “Art can’t stand still,” she asserted as though rote-repeating a Commandment. “We have to progress and move on.” “Move on?” I enquired, baffled. “Where to?” She believed it to be an incontrovertible truth that in order for a work of art to be taken seriously it had to “progress” beyond what had been done before. If it didn’t it wasn’t worth registering; indeed to repeat what had already happened was in her eyes scarcely less than a crime. I told her I had no idea what she was talking about and that her conviction that only “the new” could be important or enjoyable played no part in the way I looked at or interpreted any kind of art past or present.”

This conversation epitomises the worrying way in which the basic thoughtlessness of the classic modernist standpoint continues to remain entrenched. In saying that, the sentiments expressed by the young artist could be encountered just as easily at the Australia Council or National Gallery of Australia. I intend no particular disparagement to either body. As is clear from the confidence of the young artist’s attitude, she feels – so far as art goes – that the idea that novelty is automatically a virtue in itself has been legitimised sufficiently to make further debate unnecessary. In pursuit of this notion, it may be instructive to look at the kind of means which first seemed to legitimise and thus institutionalise such an idea. I quote from Herbert Read, who later received a knighthood and was a highly influential figure in promoting the basic precepts of modernism not only in Britain but internationally. The words are taken from Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting (1959), a

book which for decades was not merely a standard textbook but also something of a bible on art history courses. The author explains why he has excluded various highly respected artists from his book: “For a similar reason I have excluded realistic painting, by which I mean the style of painting that continues with little variation the academic traditions of the nineteenth century. I do not deny the great accomplishment and permanent value of the work of such painters as Edward Hopper, Balthus, Christian Bérard, or Stanley Spencer (to make a random list); they certainly belong to the history of art in our time. But not to the style of painting that is specifically “modern”.”

The crucial point to note here is that, of the two legitimate and commonly encountered meanings given to the word modern, Read chose style and attitude rather than period as the basis for his exclusions. Thus artists who are clearly – and unavoidably – modern in other respects, such as Hopper and Balthus, are excluded solely on the grounds of style, thus effectively making formal radicalism the most important index of quality whether for inclusion in Read’s own book, a “modern” collection or a “modern” museum.

Read, of course, was not solely to blame for what has subsequently happened. Yet, as a direct consequence of attitudes like Read’s, there is not a single painting by Edward Hopper in a British public collection and only one damaged example by Balthus. In short, we see how easily one of the two great traditions in art – the continuous – was effectively marginalised and banished. By contrast to the treatment of Hopper and Balthus – two of the great figurative artists of the twentieth century – by British public galleries, even the most inconsequential and third-rate artists from overseas have been collected avidly and in depth for British public collections provided only that they met with Read’s canon of style.

A further, contributing factor to a profoundly unsatisfactory state of affairs is that it has been widely believed by the unthinking that endless formal novelty was inexorably dragging art onward and upward to some unspecified apotheosis. Indeed, that is what the “rhetoric of radicalism” has been consistently promising all of us but which has, of course, never been fulfilled.

The meaning we attach to the word modern is vital to the future of art; in short, contrary to what modernists believe, novelty of style and attitude is not and never can be a virtue in itself in art or in any other area of life, since all change can always just as easily be for the worse as for the better.

Such a point ought to be self-evident philosophically and – if you are tempted to doubt me – ask yourself whether you believe that radical moral behaviour is automatically superior to established moral codes.

Sadly for the health of our culture, the fallacy inherent in what I describe as the “novelty trap” has been welcomed and endorsed by almost any cultural body you can think of and most notably, of course, by our Western “modern” museum culture itself.

What is wrong with such culture boils down, as I have suggested already, to a harmfully erroneous idea of what modern ought to be held to mean in relation to the arts. In fact, the meaning we attach to the word needs to be entirely neutral – that is, favouring neither radicalism nor continuity in art over each other. In order for this to happen, the meaning we give to the word modern in such a context has to relate solely to period and nothing else.

I sense that such a fundamental change of emphasis would be favoured not only by most interested members of the public but also by a majority of working artists of all kinds. In short, it is in the interests of only a small – if extremely vocal – minority to try to sell novelty in any of the arts as an automatic virtue.

Imagine for a moment what might have happened if all the publicly funded art galleries in the world which have collected the art of the past 100 years had been obliged by their charters to deal even-handedly in their collecting policies between art which reflected the best of the continuous as well as radical traditions. One certain result would be that the art on view would be much more varied and interesting – as well as less inaccessible and irritating, on the whole – to those who are obliged, whether they like it or not, to fund such institutions through their taxes. I am not advocating anything which could be described as a greater degree of populism here. Proper standards of achievement should be demanded of those who work in more traditional and continuous ways just as they should be – but frequently are not – of those who flirt consciously and often for advantage with the latest fashions.

The storerooms of Australia’s state and national galleries are full to overflowing already with embarrassingly ephemeral art “bought in haste and repented at leisure” by curators, committees and directors who have convinced themselves that novelty must be a virtue somehow, especially where works lack any other obvious merits. Another instant and highly beneficial effect of my suggested change of emphasis would be on art education. Artists desperate to learn time-honoured skills would no longer need to feel disadvantaged academically – as they certainly do now – or in terms of their subsequent careers by not being at the “cutting edge”. Indeed, as an absolutely typical example of the tiresomely familiar “rhetoric of radicalism”, expressions such as “cutting edge” are overdue for permanent banishment – along with the entire delusion in art of modernistic “progress” itself.

In relation to Blue Poles, imagine the relief of many who might no longer feel any obligation to see in it qualities which were never there, but to view it rather as an interesting example of a formerly fashionable way of regarding the evolution of art, once promoted vigorously by an American cultural establishment desperate to create credibility for itself.

To those fortunate enough to be familiar with the greater history of art, both Blue Poles itself and the whole, aberrant notion of “total” abstraction in art will continue to appear as very small blips on a very large screen. For the rest, a serious attempt to get the history of art into some kind of focus represents an ideal starting point for showing genuine concern for the future of art in this, or any other country.

This article first appeared in Quadrant, a literary and cultural journal published in Australia (10 issues a year): https://quadrant.org.au/

Giles Auty

The Jackdaw March-April 2015