Most YBAs achieved prominence by recasting genuine avant-garde art in a palatable commercial form, influenced by advertising and pop culture, and served up to a credulous public largely ignorant of the original sources of the art. (Something Julian Stallabrass discusses in his book High Art Lite.) Jenny Saville was seen as one exception by virtue of the facts she studied in Glasgow, not Goldsmith’s College, and painted figures representationally in a non-ironic manner. Yet on closer study, Saville is not dissimilar to her YBA peers. Since paintings were acquired from her college studio, 404

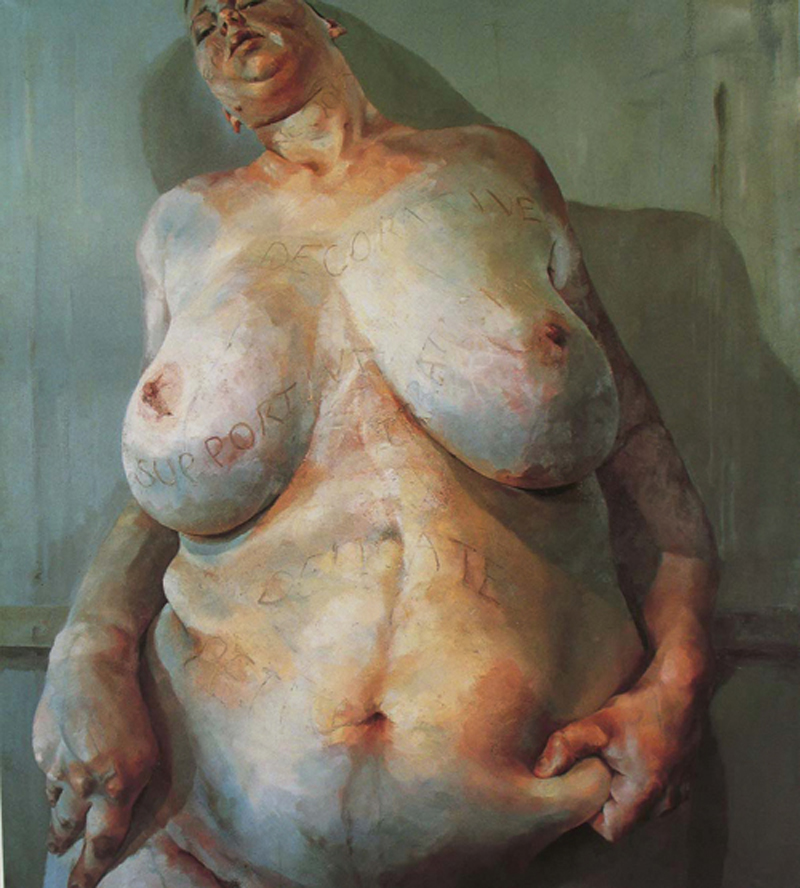

Saville’s paintings have changed from billboard Lucian Freuds to hybrids of Freud, Bacon and de Kooning. Her painting rests upon adapting recent art and presenting it in a more extreme form (larger than that by the original artists), shorn of the original art’s foundations and complex origins, just as the art of other YBAs does.

The paintings have been described as “monumental” by writers

The resource requested could not be found on this server!

who cannot differentiate between monumental and big. Likewise, painting something from a very close viewpoint (a Saville tic) does not convey monumentality or help us comprehend the mass of a figure. Monumentality has nothing to do with size; it has

404 Not Found

do with the impression of size, which can be conveyed through adjusting the size of a motif relative to the picture surface, elimination of detail, lowering the observer’s viewpoint of the motif, reduction of colour, simplification of form and emphasis on the mass of a motif. Picasso could achieve this concisely in modestly sized paintings and drawings (those of the Boisgeloup period, the Dinard bathers and the Gosol figures), as can any artist who applies the principles. Painting fat figures on large surfaces tells us nothing about fatness but it reveals the painter’s insecurity, her need to bolster insubstantial depictions of bodies by expanding them to cinema-screen scale.

Looking at Saville’s paintings is like opening the sketchbook of a teenage art student. There is the preoccupation with “body issues”, a reliance on photographs, the modish twist of gender-change surgery and emulation of the most obvious recent painters of the nude. Saville fails to realise that some great painters

are bad influences and looking at artists you paint like (or aspire to paint like) can be damaging practice. (The recent drawn pastiches of Leonardo

Jenny saville and the theatre of self-importance: Alexander Adams examines the reputation of one of the original young British artists

Most YBAs achieved prominence by recasting genuine avant-garde art in a palatable commercial form, influenced by advertising and pop culture, and served up to a credulous public largely ignorant of the original sources of the art. (Something Julian Stallabrass discusses in his book High Art Lite.) Jenny Saville was seen as one exception by virtue of the facts she studied in Glasgow, not Goldsmith’s College, and painted figures representationally in a non-ironic manner. Yet on closer study, Saville is not dissimilar to her YBA peers. Since paintings were acquired from her college studio,

404

Saville’s paintings have changed from billboard Lucian Freuds to hybrids of Freud, Bacon and de Kooning. Her painting rests upon adapting recent art and presenting it in a more extreme form (larger than that by the original artists), shorn of the original art’s foundations and complex origins, just as the art of other YBAs does.The paintings have been described as “monumental” by writers

The resource requested could not be found on this server!

who cannot differentiate between monumental and big. Likewise, painting something from a very close viewpoint (a Saville tic) does not convey monumentality or help us comprehend the mass of a figure. Monumentality has nothing to do with size; it hasLooking at Saville’s paintings is like opening the sketchbook of a teenage art student. There is the preoccupation with “body issues”, a reliance on photographs, the modish twist of gender-change surgery and emulation of the most obvious recent painters of the nude. Saville fails to realise that some great painters

are bad influences and looking at artists you paint like (or aspire to paint like) can be damaging practice. (The recent drawn pastiches of Leonardo