Michael Daley

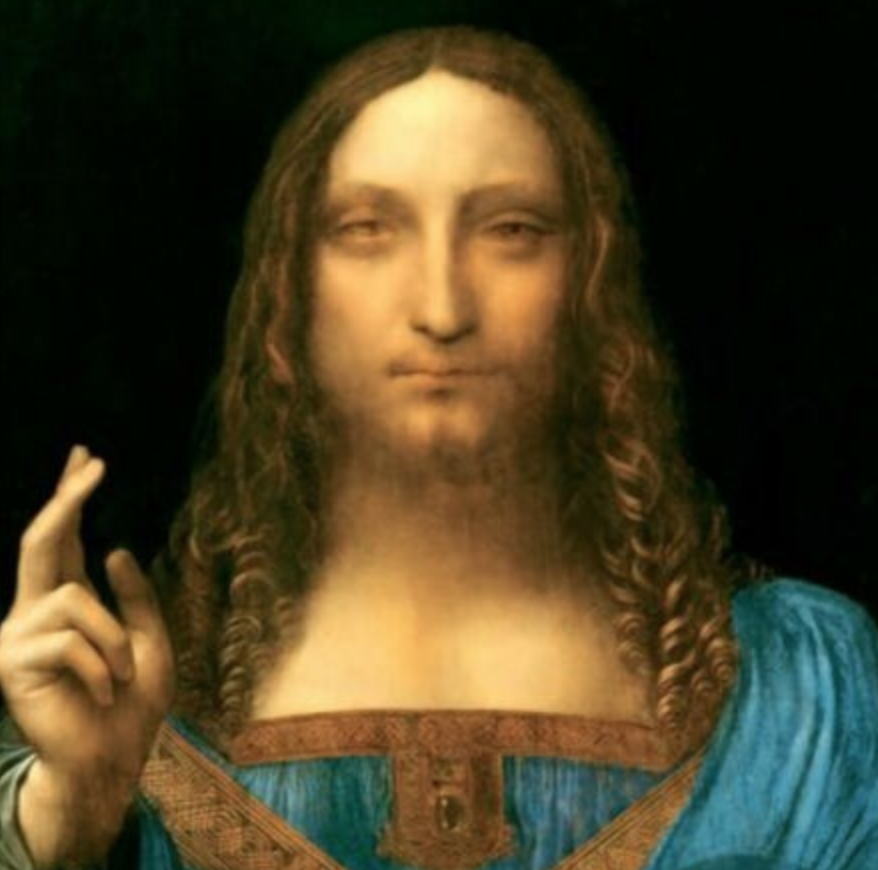

Questions proliferate on the disappeared $450 million Leonardo Salvator Mundi. Where is it? Who owns it? Who still believes it a Leonardo? Will it be exhibited this year at the Paris Louvre’s big Leonardo exhibition, as promised? Can it be true, as an artnet blogger now claims (on the claimed say-so of “two principals involved in” Christie’s 2017 sale) that the painting was removed on the night of the sale to be installed on the yacht of Saudi Arabia’s supreme ruler, Mohammad Bin Salman? Does Christie’s know more about this imbroglio than it has disclosed? Will the Salvator Mundi ever be seen again?

In The Last Leonardo, Ben Lewis contributes hugely to knowledge of the picture’s shadowy emergence and subsequent near-mythic elevation. We now know the picture was bought not for “around $10,000”, as claimed, but for $1,175 – for less than the low estimate of $1,200-1,800 on a work described as being “after Leonardo da Vinci” at the St Charles Gallery, New Orleans. We now know that gallery closed down after the Salvator Mundi’s sale and reappeared under the same name but without previous records. We now know Christie’s turned the picture down in 2005. We know the “consortium” of buyers initially comprised Robert Simon, a New York dealer and Alex Parish (a freelance dealer and online picture scout for the Richard Green dealership). We know that before, during and after being exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12 as an undisputed autograph Leonardo, the picture was on the market and numerous attempts to sell it privately to museums for between $80 million and $250 million failed.

Lewis discloses that it was variously rejected by: the Qatari royal family; the Hermitage; the Getty Museum; the Museum of Fine Arts Boston; the Vatican; Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie; and a German auction house whose Leonardo advisor, Professor Hans Ost, was and remains “very sceptical about the attribution”. The initial consortium was running out of money and afraid to offer the picture for auction. As Parish put it to Lewis, “there’s not a deader-in-the-water [work?] than a picture which you put up to auction and then bombs… where do you go from there? Absolutely dead.” Somehow, despite all failures, unimaginable success was to follow.

Deliverance began with a third consortium member: “An offer of help came in 2010 from a reputedly well-connected New York old master dealer, Warren Adelson, who has a gallery in a magnificent uptown townhouse. ‘I made a proposal to Robert and Alex to buy a share of the picture,’ Adelson says, ‘because I wanted to run with the ball and help them sell it.’ He negotiated a 33 per cent stake in the painting in return for a $10 million advance payment. It was accepted. As Robert Simon put it ‘there were a lot of expenses. The photography and the storage were expensive. When we insured at its value the insurers wouldn’t allow me to keep it in the gallery. It had to be kept in a vault at an art storage facility. There were my research costs, going to Europe five times, and Milan five times, and London and New York, and going and checking the libraries. Dianne [Modestini, the restorer] was helpful in not requiring us to pay everything in advance.’”

Lewis wryly observes “nothing in the known universe, no item, no object or quantity of material, has ever appreciated as fast as the Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo da Vinci” but, even with a war chest, and Adelson on board, the going remained rough. The picture was offered to the Dallas Museum (for a rumoured $125 – $200 million). The museum’s new director, Max Anderson, was enthusiastic about the chance to “‘acquire a destination painting’ that would draw crowds to the museum.” Parish told Lewis: “We were strung along by him for some time … at the eleventh hour they offered just $40 million and $25 million of that was meant to be a swap with another painting. Apparently some of those Bible Belt people had little or nothing good to say about the picture. One guy – I won’t tell you who – said, ‘Boy, that is one faggy-looking picture of Jesus’ or something to that effect. I was really like, ‘O-o-oh, great. This is going so well.”

Despite the astronomical leg-up inclusion in the National Gallery’s major Leonardo exhibition as a rediscovered lost autograph Leonardo prototype painting, this Salvator Mundi remained unwanted by museums and could not be risked at auction. Partial success – in the consortium’s inflated terms – was only achieved in 2013 with a controversial lawsuits-generating private sale through Sotheby’s to a Freeport owner who bought at $80 million and immediately sold on to a Russian oligarch for $127 million.

What then would carry the picture over the line so spectacularly in 2017? When Christie’s got its second chance, it launched a global promotional blitz that rested on two planks: the authority of a claimed unusually broad consensus of endorsement among art historians; and, an absurdly inflated and unfounded provenance taken from the National Gallery’s own unfounded claims that rested on the then – and still – unpublished researches of Robert Simon. ArtWatch UK exposed the unsoundness of Christie’s provenance the day before the sale.

Lewis gives an especially attentive account of the precisely focussed means by which this seeming sufficiency of art experts was enlisted. With the single exception of Professor Martin Kemp (who spouted statements galore and made a promotional video for Christie’s immediately ahead of the sale to counter our criticisms) almost none of the listed scholars and curators had then – or has since – gone on record giving reasons for holding the painting to be an authentic autograph Leonardo prototype for all other Salvator Mundi versions. When Lewis asked the consensual scholars he “was not able to verify the verdicts of all the art historians listed in Christie’s catalogue.” His account of how the tongue-tied dozen scholars were assembled is molten:

“Robert Simon was well aware that he needed to be strategic and accumulate the right allies if his painting was to be authenticated as a fully-fledged Leonardo. ‘Part of the reason for the secrecy was the mechanics, if you will, that Bob had to employ in order to get the utterly fantastic consensus that he compiled,’ says Alex Parish … After the initial period of restoration [there being quite a number – see Figs. 2 to 8], Simon and Parish began showing the picture to close contacts. The first to see it was Mina Gregori, not a Leonardo expert but a close friend of Simon’s who had made some hotly contested attributions to Caravaggio in the past. She came to see the picture in New York in November 2007, and said nothing at all while she was standing in front of it, but as Simon walked back to the lift she turned to him and said, with an Italian sense for melodrama, ‘È lui’ – It’s him.”

Gregori was a good first choice. The owner of the Martin Kemp-supported La Bella Principessa drawing, Peter Silverman, gave this account of Gregori’s endorsement of that other would-be Leonardo in his 2012 memoir Leonardo’s Lost Princess: One Man’s quest to Authenticate an Unknown Portrait by Leonardo da Vinci:

“We had become close friends with Mina over the years, and she frequently stayed with us when she visited Paris … I asked her to look at the portrait again, telling her, ‘Mina, people are saying it could be Leonardo. Please sit and study it carefully and give me your honest opinion’ … Mina remained bent over the portrait for a very long time. Finally she called me to her side. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘It is Leonardo. Allow me to be the first to say so formally.’ I handed her a black-and-white photo, and she wrote the attribution on the back. I still have it.”

Lewis frequently encountered un-clarity and contradictions: “Several curators and restorers from the Metropolitan Museum saw the partially restored Salvator Mundi in early 2008, but it is not clear what exactly was said about the painting. According to Robert Simon and Christie’s, a majority of the Met experts agreed they were looking at a Leonardo. One of its Italian renaissance specialists, Keith Christiansen, certainly did, and still does. Another senior staff member, Andrea Bayer, deputy director for collections, told me she would not comment on the painting. One senior academic source close to the Met told me, on condition of anonymity, that ‘The Met curators don’t believe that it is by Leonardo. One curator told Simon that the Met would be glad to accept the painting as a gift for study purposes. That means they thought it was a wreck and not by Leonardo.’ Another highly placed museum source informed that one of the Met’s curators ‘judged the painting a Leonardo but didn’t want it in his collection because of its condition’. If the museum’s specialists did consider the possibility that it was a Leonardo, it’s unusual that they made no attempt to make Simon an offer for it at the time – or since.”

Next stop for Simon was Nicholas Penny, then head of sculpture at the Washington National Gallery who had recently bought a sculpture for the museum from Simon. “‘Robert’s had quite a lot of dealings with me, and I think he probably knew that I was not frightened to stick my neck out,’ Penny told me. Simon showed Penny the painting, and he responded, ‘You have a really interesting problem.’ By that, he did not mean the attribution was an issue. He was referring to the difficulty of establishing widespread agreement in the art historical community for new attributions.” Penny passed the baton to Luke Syson who was organising the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition. Syson shared his newly appointed boss’s judgement, telling Lewis in Kempian language: “It had that sense of how the natural is assembled to make the supernatural. The picture seemed to hover somewhere between our realm and the supernatural.”

Syson and Penny saw an opportunity for a dramatic pictorial debut and an accompanying risk: “They knew that exhibiting a painting such as the Salvator – newly discovered, with uncertain attribution and on the market – would break a universally accepted convention of public collections not to legitimise or promote entrants to the field. To overcome this hurdle, Syson came up with a high-stakes solution. He organised a seminar, a gathering of the world’s top art historians to examine the Salvator in London ‘with an open mind’.” So, a disinterested scholarly perusal was in prospect? Here’s how Lewis saw it:

“Five great Leonardo experts attended this meeting. From Milan came Professor Pietro Marani, who had supervised arguably the most challenging restoration in art history, that of the Last Supper … Also from Milan was Maria Teresa Fiorio, who had run two of that city’s major museums and was an unrivalled specialist in Leonardo’s assistants and pupils. Carmen Bambach, the curator of drawings at the Met, had already seen the Salvator in New York on several occasions. [And was one of a quartet of distinguished scholars who rejected the attribution in reviews of the National Gallery exhibition.] From Washington, DC … came David Alan Brown, the revered curator of Italian paintings at the National Gallery of Art, who had long ago in his PhD thesis expressed his belief in the existence of a ‘lost Salvator Mundi’ by Leonardo, depicting ‘a mature bearded Christ … frontally posed and strongly lit from the left against a dark background with his right hand raised in blessing and his left hand holding a globe’.”

In so contending, the student was then putting down a challenge to the great Leonardo scholar, Ludwig Heydenreich who, in a major study on the Salvator Mundi problem had concluded there was no indication that Leonardo had painted a prototype Salvator Mundi from which all other versions derived. In 1978 another American student, Joanne Snow-Smith, proposed that one version – the de Ganay – was the missing autograph Leonardo prototype painting. In 1982 she produced a book of advocacy (The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo da Vinci), which also failed to gain acceptance. However and astonishingly, much of her unsupported confection of a French royal provenance for the de Ganay version was lifted and applied by Syson in his catalogue entry. (Lewis believes the National Gallery had mistakenly switched versions and that Christie’s simply followed suit: “Luke Syson has since told me that he was mistaken to include this in his catalogue entry”. Lewis reports that research he commissioned shows that, contrary to Snow-Smith’s claim after Heydenreich’s death, the great scholar had not endorsed her thesis and, in truth, had rejected it in scholarly code.

The last scholar to arrive at the Syson seminar (Penny did not attend) was Martin Kemp. Conspicuously absent, Lewis notes, was (our colleague) Jacques Franck, “a Leonardo expert who was a trained painter rather than an academic, and who had advised Syson on the restoration of the Rocks.” Another omission “the most surprising, was Frank Zöllner. A professor of art history at Leipzig, Zöllner was the author of the best-selling, multi-edition catalogue raisonné of Leonardo’s paintings.” Lewis suggests a possible reason for Zöllner’s absence. He had recently written: “mention must be made of the increasing attempts, above all in recent years, to attribute second and third-class paintings to Leonardo’s hand. In this context it should be noted that the catalogue of paintings presented here is definitive. While there may be works circulating in the fine art trade that stem from Leonardo’s pupils, the likelihood of an original by the master himself is extremely small.’ Syson says that leaving Zöllner off the guest list in London was, in retrospect, ‘a mistake’.”

A mistake of a not uncommon kind at the National Gallery, it would seem, when attributions are afoot. On 8/9 November 2002 a symposium was held at the Gallery at which 25 art scholars and experts examined another small painting in the conservation department to determine whether a version of the very many Raphaelesque Madonna of the Pinks was the autograph Raphael original, as was being proposed by the Gallery’s Italian Paintings curator, Nicholas Penny. The Gallery later claimed that all present shared Penny’s judgement that the Northumberland version, which had been on display at the Gallery for ten years, was the original autograph Raphael. One Raphael expert excluded from the occasion was our late colleague in ArtWatch, Professor James Beck of Columbia University. As Beck wrote in his 2006 book, From Duccio to Raphael: Connoisseurship in Crisis, “Since the picture … was essentially on the market, a consensus among experts was highly desirable. An undocumented object that lacks the appearance of a consensus will not bring top prices and will rarely be treated seriously. In the past such an accord might have taken years to accomplish, but in today’s globalized world it can occur quickly, especially with the prodding of the public relations apparatus, amply available in world-class museums like New York’s Metropolitan and London’s National Gallery.”

At the National Gallery’s Salvator Mundi seminar, Lewis notes, “No minutes were taken … No declaration of any kind was signed … No official announcement was issued after it ended. There was no formal process by which the attribution of the painting was conducted. The National Gallery did not ask to have the painting left with it to be examined … as the Albertina Museum and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna had done with the Bella Principessa, before reaching a negative conclusion … After the meeting, Syson informed Nicholas Penny that the experts had agreed that the painting was indeed by Leonardo himself … Two weeks after the meeting, Penny contacted Simon and told him that the art historians had judged his painting to be a Leonardo … Penny formally asked if the National Gallery could borrow the painting for its exhibition three years hence, and also asked him to keep it a secret until then.”

The members of the National Gallery Salvator Mundi seminar had also been sworn to secrecy – as Kemp puts it in his memoir, Living with Leonardo, “All of the witnesses in the gallery’s conservation studio were sworn to confidentiality, and the painting travelled back to New York with Robert. It was becoming a ‘Leonardo’.” Beck had observed with the National Gallery’s Raphael symposium, “No polling of the invitees’ views concerning the putative author of the Northumberland Madonna was conducted … at least as far as I have been able determine. The National Gallery director reasoned that since none of the people who attended … expressed doubts at that time about Raphael’s authorship, they all favoured it, interpreting silence as agreement.” Lewis continues, “However the art historians who attended the National Gallery meeting did not in fact reach an official attribution or an informal consensus about the Salvator Mundi. Nor were they asked to. ‘I have never issued an official opinion on the Salvator Mundi, and in any case, I have never been asked to do so,’ Maria Teresa Fiorio told me. ‘I discussed the painting informally with colleagues, and I do not know by what means my opinion was made known. If the Salvator Mundi was exhibited as an autograph work at the National Gallery, then that was an autonomous decision by my London colleagues.’”

On the Penny Raphael symposium, Beck reported: “Although an overwhelming majority of the participants were persuaded, and hence a credible consensus was achieved, the claim of unanimity is unwarranted. I learned that at least three of the original 25 do not agree that picture is an autograph painting by Raphael. Indeed, one participant told me with indignation that he had spoken out against the attribution at the symposium itself* [*It is indicative of the climate of such encounters this dissenter insisted that I not identify him]. For the connoisseur the lesson of the Northumberland Madonna must be: beware of the consensus. Factors outside the specific issue can be determining factors, including personal friendships, national and institutional loyalties, and the distinction and power of the museums represented. Arguably in the case of the Northumberland Madonna the entire Anglo-American Art Establishment was co-opted, including Christie’s auction house by the presence of one of its staff, while Sotheby’s was directly involved and did take credit for the sale to the National Gallery, according to its own advertisements. What makes this consensus attribution so intriguing is that until 1991 an equally solid consensus among Raphael scholars held that the picture was nothing more than a good copy **[**The observation was made to me by Michael Daley.]”

Lewis noted “The final score from the National Gallery meeting seems to have been two Yeses, one No, and two No comments.” He adds “For three years nothing was heard of the National Gallery meeting. Then in the summer of 2011, a few months before the blockbuster Leonardo exhibition opened, the curtain was finally drawn back. Simon issued a press release on 7 July. ‘A lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci has been identified in an American collection,’ it began. He then carefully listed the names of the illustrious art historians to whom he had shown the painting … Simon claimed that there had been ‘an unequivocal consensus that the Salvator Mundi was painted by Leonardo, and that it is the single original painting from which the many copies and versions depend … The Salvator Mundi is now privately owned and not for sale.’” Penny was to be hoist with his own petard: “Penny and Syson knew that this was not factually correct, although it is highly unusual for a public institution to show a painting that it knows is for sale. ‘I did know, of course, that the picture was potentially on the market when we borrowed it,’ says Penny. ‘Some people have professed to be astonished by this, but I’m pretty sure I would have discussed this with the relevant trustees and the chairman’ … Luke Syson told me, ‘I catalogued it more firmly in the exhibition as a Leonardo because my feeling was that I was making a proposal and I could make it cautiously or with some degree of scholarly oomph.’” David Ekserdjian, a Gallery trustee at the time, confirmed to Lewis that he supported the attribution. The Board Chairman was Mark Getty.

Lewis’s conclusion startles: “Where the institutions of art have rules they are often the wrong ones – out of date, no longer fit for purpose. Museums, for example, are not by convention, allowed to exhibit a work of art that is on the market or to show a newly discovered one with a doubtful attribution – the source of much of the controversy over the Salvator Mundi. But as exhibitions and museums multiply, while the stock of old paintings remains much the same, it is unreasonable to expect curators not to look for pictures with surprises and controversial backstories to put into their shows. Such disputes are part of the reality show of art …”

Best to treat art as its own reality. Cutting corners on connoisseurship would do the art world no favours.