Another month, another book on the contemporary art economy, this time from an overlooked perspective. The New Economy of Art, a joint publication by DACS and Artquest, looks at the art market from the POV of the average artist. Not surprisingly, it finds plenty to puzzle over.

The conundrum it addresses is clearly set out in the preface by editors Gilane Tawadros and Russell Martin. “The art world is in crisis,” begins the first paragraph; “The art world is in the best shape it has ever been,” begins the second. The question of how these conflicting statements can both be true at the same time – “the disconnect between how artworks gain financial value even while their makers are poorly, or hardly, paid.” – is the mystery the authors of its six essays try to solve.

Two weeks before the book came out, Christie’s New York achieved an all-time auction record for its November postwar and contemporary art sale, in which a Warhol Triple Elvis hit the jackpot – kerchung! – at £51.6m – and a row of Four Marlons paid out a further £43.9m. Both, appropriately, had previously hung in a casino in Aachen. The result was hailed by international head of post-war and contemporary art Brett Gorvy as confirmation of “a virtuous cycle of confidence in the art market”. Another season, another reason for making whoopee.

On the other side of the art market, meanwhile, a more vicious cycle is in operation. The book’s authors quote the usual dismal statistics. It’s depressing enough to learn from the 2011 survey by the Centre for Intellectual Property, Policy and Management at Bournemouth University that UK artists earn a median wage of £10,000 – unchanged for 20 years – without discovering that the statistic includes designers, illustrators and photographers, and that the top 7% earn 40% of the total. Artists now officially rank as ‘marginalised makers’, a marginal constituency politicians aren’t fighting over. The economist Alan Freeman quotes figures showing our ‘creative economy’ growing faster than any other UK production industry, employing 2.5 million people and accounting for 5.2% of gross value added – but take out all the advertising, marketing, fashion, IT and other people he counts as ‘creative specialists’, and the fine artists are still scratching around on the margins.

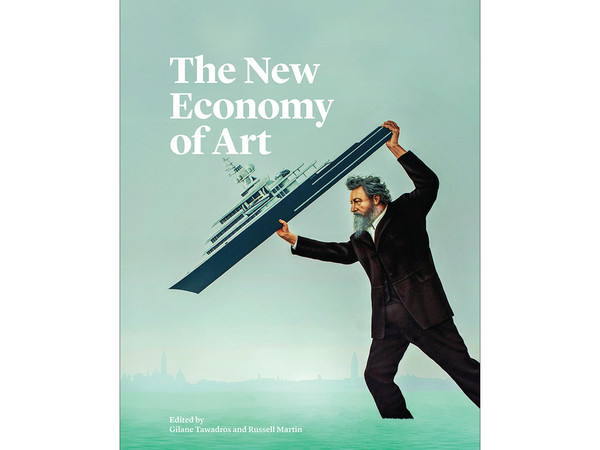

The book’s cover reminds us that there is nothing new in this. It reproduces Jeremy Deller’s mural from the 2013 Venice Biennale picturing William Morris as a Victorian Poseidon hurling Roman Abramovich’s superyacht into the Venetian Lagoon. The mural’s title ‘We sit starving amidst our gold’ encapsulates the argument at the heart of the book while reminding us that Morris said it all before, and better. Compare Freeman’s dewy vision of a creative utopia “in which shared values, achievements, hopes and aspirations replace brute greed to lay foundations on which the true individuals of the future can confidently build the new worlds of their choosing” with this trenchant passage from Morris’s lecture Art Under Plutocracy: “So long as the system of competition in the production and exchange of the means of life goes on, the degradation of the arts will go on; and if that system is to last for ever, then art is doomed, and will surely die”. Only the substitution of association for competition, believed Morris, could “give an opportunity for the new birth of art, which is now being crushed to death by the moneybags of competitive commerce.” In the war of words, Morris wins hands down.

Still, the book contains material which, if not revolutionary, is astonishingly inflammatory for a publication part-funded by the Arts Council. Have they read it? It has a quiet way of dropping bombshells. One is the casual mention by management consultant Keir McGuinness of the apparently generally accepted practice whereby “the decision of whether a [public] gallery will take a show or not depends upon whether you [the artist’s dealer] will make a financial contribution and the person who makes the largest financial contribution gets the shows”. Another is a statistic cited from AN’s recent Paying Artists report that “71% of artists receive no fee for publicly funded exhibitions and nearly 60% do not even have their expenses covered”. This against the background of an international art industry which, arts consultant John Kieffer points out, has a turnover of just under £40bn, with the UK’s market share of 20% amounting to three times the combined budgets of the English, Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish culture departments.

But the real eye-opener is the essay by curator Lynda Morris. Born in 1947, Morris is old enough to remember the heady days of the 1960s when a newly international avant-garde was promoted by dealers who were themselves artists, lived like artists on air and were perceived as having ‘moral authority’. What an antiquated concept that now sounds. After reading Morris’s analysis of the process whereby the present nexus of curators, industrialists, bankers and property developers took control of the art world, it seems to belong to another era.

Morris pinpoints Thatcher’s appointment of Richard Rogers as chair of Tate Trustees in the 1980s as the start of the cultural ascendancy of architecture over art. “It was the moment in late Thatcherism when the State no longer provided social housing and, instead, the national lottery, a new arm of the gambling industry, enabled museum directors and their trustees to start to plan Palaces of Culture.” A proposal to regenerate derelict buildings for low-cost studios, housing and artist-led galleries put forward by officers of the then Arts Council of Great Britain – in association with artists’ collectives ACME and SPACE – was kyboshed by property developer Peter Palumbo, who as chair of the ACGB from 1988-94 presided over the drafting of the rules for National Lottery funding, including the ‘subsidiarity’ clause ensuring that money is allocated only to new projects and thus funneled towards developers and architects rather than artists. Artists are wonderful at sprinkling the fairy dust that turns urban wastelands into developers’ goldmines, but once the gold has been extracted the fairies can piss off and take their dust elsewhere. Prices for a ‘premium apartment’ in Neo Bankside, the new residential development overlooking Tate Modern designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour – formerly Richard Rogers Partnership – start at £4.5m.

“We seem to have drifted from a market economy to a market society,” comments John Kieffer. It’s a form of society Margaret Thatcher would have recognised, but not William Morris. “It is this superstition of commerce being an end in itself, of man made for commerce, not commerce for man, of which art has sickened,” he wrote in Art under Plutocracy. Art under kleptocracy has brought no improvement. It has been left to President Xi Jinping to uphold moral values, warning Chinese artists last October not to follow the “stench of money” or “lose themselves in the tide of market economy” which the rest of the People’s Republic is happily riding.

Are artists and Gordon Brown now the only people on the planet still expected to possess a moral compass? That could explain the disconnect highlighted by this book. If our market society is wholly reliant on artists for moral orientation, it has good reason not to seduce them with the stench of money, ie pay them. You could almost call it a virtuous cycle.

Laura Gascoigne

The New Economy of Art, edited by Gilane Tawadros and Russell Martin, published by DACS, £14.99