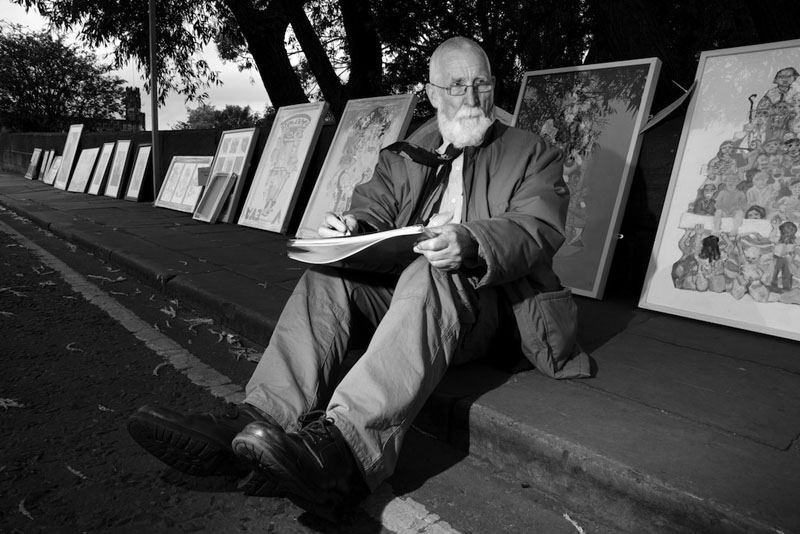

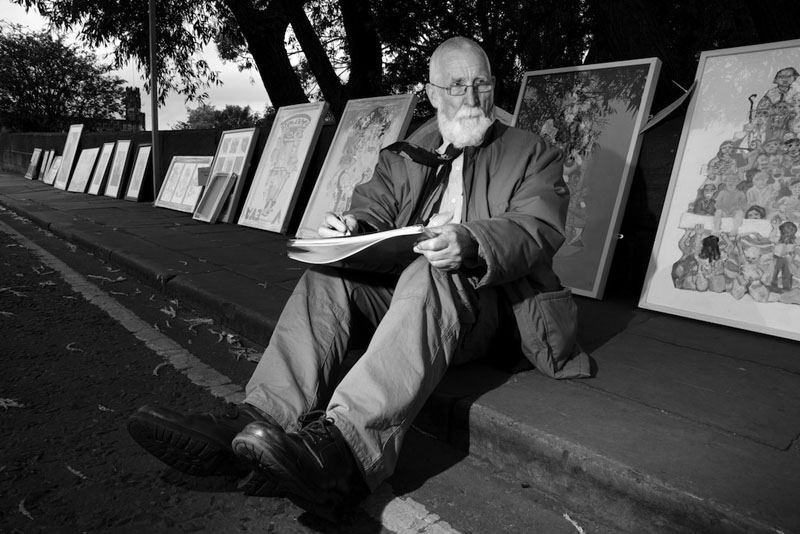

Brian Lewis, Pontefract’s poet laureate and a painter to boot, bravely exposed the neglect of local artists when the visiting functionaries of State Art arrived for the opening of the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield

In the cultural war which challenges the dominance of the London art world we are the first shock troops of a new guerilla army which urges artists to get out onto the streets and protest by using art to confront art.

What follows is an account of what happened when we attacked the Hepworth in Wakefield using a 6,000-word didactic leaflet, 21 paintings and a small piece of sculpture called Don’t Have Any More Mrs Moore. We called our guerrilla attack Operation Good Morning Mr Courbet.

We had been led to believe that Prince Charles was coming to open David Chipperfield’s £35 million gallery in Wakefield and that for security reasons the police were likely to clear the nearby Chantry Bridge prior to his arrival. Arguing that they would find it more difficult to evacuate us if our two advertisement boards and framed pieces were already in position, we tied 8ft x 3ft horizontal boards to roadside railings and bollards. Both faced the Hepworth’s entrance and read ‘Alternative Exhibition – Free University of Chantry Bridge, Wakefield’.

The Free University reference was understood in parts of the district. We had recently held an exhibition six miles away in the Heritage gallery in the ex-mining town of Castleford. At its Bridge Arts Gallery we had workshops, a rolling exhibition programme, and were also offering writing, publishing events and a UK premiere of a piece of music composed by the Professor of Creative Technology at Leeds Met University based on an ex-miner’s poem. In Castleford we were called the Free University of Castleford on Aire. The new name, The Free University of Chantry Bridge, Wakefield was chosen because it suggested that our rabid arts collective had seen the Hepworth, been shocked by its appearance, and pupped.

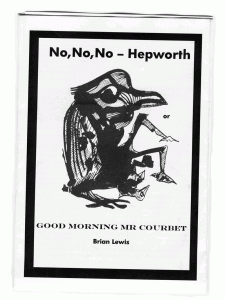

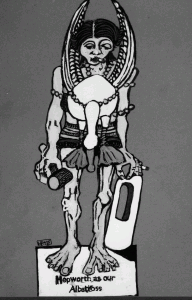

Our pamphlet was called No, No. No – Hepworth because it is direct, but the sub-heading was chosen because it is the title of a painting which shows a local patron doing honour to a local journeyman artist. Courbet is also appropriate for another reason. When he was refused hanging space at the 1855 Paris Exposition Universelle he erected his own temporary structure next door to the main pavilion and showed 40 of his own pictures, including Burial at Ornans and The Artist’s Studio, which now hold pride of place among the Grands Machines of the Louvre.

The Chantry Bridge exhibition was mobile and although this was not explained to anyone the west end of the bridge area was its holding bay. The plan was to draw attention to our leaflets and pictures by shifting some of the 21 framed images close to the grass by the pedestrian bridge which every visitor would pass over that night on their way to the opening at 6.00pm. Using this location we would hand visitors the No, No, No – Hepworth or Good Morning Mr Courbet 6,000-word essay-cum-tract. We had planned a pincer movement attack: paintings to look at and a tract to read.

This had been printed in an edition of 250 by a local printer (localism is always a good greasy slice of halal to slap across the chops of a prestigious gallery) and consisted of 16 numbered pages which came folded from a piece of A3 paper. It cost £75 to print. We did the design ourselves.

In all ways it was massively non-PC and went against all the rules of modern advertising. It was not in colour, recognized no sponsors and took little regard for people who had dodgy eyesight. It was knocked up by a couple of blokes in a basement in Pontefract who had combined ages of 136 years.

We knew that most people wouldn’t read it, but a few might. Online petitions bother no one and make it seem that you are doing something when you’re not. Those in authority might read on and our leaflet was aimed to get up their nose and along with the paintings make us visible. The size of the tract was very important. Mail goes from the hall floor into the recycling box with scarce a glance. This went directly into the pocket or shoulder bag.

Drums and trumpets sounding outside a critical arts board meeting has a similar immediacy. Both loud music and tract publishing are in the tradition. Action precedes argument. Move your feet and your arse will follow, or put with more finesse by existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (he whispered little else in Simone De Beauvoir’s ear): “In the absence of certainty action must take the place of speculative thought.”

At first very little happened (we discovered there was to be no Royal Visit). A few locals stopped to talk although most were on their way to work.

I had been having an email and a ‘letters to the local newspaper’ correspondence with the leader of Wakefield MDC, Peter Box. The dialogue had been going on for about a month. From my side it concerned the need to watch the promotional data supplied by their consultants, the questioning of why we should be promoting a ‘mausoleum artist’ and the proposed programme of retrospectives by what are inevitably described as ‘eminent international artists’. I considered that even when the running of the gallery was passed onto the Hepworth Trust it would still have a call on the public purse through Arts Council England or through English Heritage. I forecast that the wider agenda of regenerating a derelict area might have a bearing on the level of financial commitment by the council.

In the middle of the night, 4.30 am to be precise, I’d emailed him and told him that two days before I’d received a telephone message. The speaker told me that the Hepworth knew there would be a demonstration on the Bridge and had offered to be some sort of broker. She said that although the Hepworth Gallery was happy with the demonstration the Council was ‘likely to take strong action’.

My email said that I had a perfect right to demonstrate. I pointed out that having done National Service, bullying or imprisonment held no fears for me. I have a big white beard and, therefore, I said, I relished the thought of police involvement and that having photographs of a Santa look-alike handcuffed would suit me fine, for at the very least a photograph would cause industrial disputes in Lapland.

The first call I received that morning came from the Constituency Manager of my MP, Yvette Cooper. Yvette had asked her to find out if Peter knew what I was doing. Presumably Peter had phoned her. I said I would phone Ms Cooper a bit later.

At nine I was joined by one of my sons carrying tea in a paper cup. He is a man who could be relied upon to argue forcibly if needed. Porl, a professional photographer, came a little later. The witnesses and two cameras could be useful.

I knew an emissary would come from the council and at 11 am, just after they had started the initial party for ‘100 very special guests’, he rolled up. Wakefield’s Deputy Chief Executive was someone I’d known for years and liked. He made the obvious point that I had a right to protest, to which I replied ‘You’re right there’. Then he said: ‘Peter says that are you aware that the Hepworth family are gathering this lunch time and today is the anniversary of her death.’

There they had me. Sentiment took hold. As soon as he said it I knew that I was not going to upset a family gathering, any family gathering, by speaking ill of granny.

I thought quickly. ‘I will not give the leaflet out today, even though the main arts gathering is on tonight, but I will not remove the paintings. On your part I want you to say that you will read the leaflet and pass copies down the appropriate line of management. This printing has cost me a good slice of this week’s pension. I will do that but only for tonight, tomorrow is another day.’

Compromise brought conciliation. ‘What exactly is your target?’ he asked. I took out the leaflet and read the back page. ‘This pamphlet’s targets are the London art world and the type of art they promote; arts consultants, their data and the withdrawal of funding from other local arts organisations. It chronicles overspending on fine arts and the consequent neglect of local artists, writers, publishers, theatre companies and museums. Hopefully it will become the start of a debate about why and how we fund the arts in the UK and how it differs from how they are funded elsewhere.’

Compromise brought conciliation. ‘What exactly is your target?’ he asked. I took out the leaflet and read the back page. ‘This pamphlet’s targets are the London art world and the type of art they promote; arts consultants, their data and the withdrawal of funding from other local arts organisations. It chronicles overspending on fine arts and the consequent neglect of local artists, writers, publishers, theatre companies and museums. Hopefully it will become the start of a debate about why and how we fund the arts in the UK and how it differs from how they are funded elsewhere.’

Ten minutes later I was talking with both the newly appointed Chief Executive and Wakefield’s senior arts officer. I was blunt and they were amiable but they listened carefully and promised to read the leaflet. I assured them that we would meet again.

They were followed by a procession of friends who knew about the ‘exhibition demonstration’ and Wakefield officers, mostly people I knew because of my work on regeneration. They told me bits and bobs about plans for the rest of the weekend and how they intended doing up the area. There were other hard-handed men and the occasional hard-hatted woman who knew about art and what they liked.

Then the police arrived. They had been sent by someone – exactly who I’m not sure – but they were fine. They informed me that I was committing the technical offence of obstructing a public highway but agreed that since I had avoided putting up a price list I wasn’t trading. They exercised their right of discretion and the right of demonstrating seemed to overrule everything. Then the last-but-one visitor came. He was ‘a Hepworth’, the only member of the family to bear the name. He was followed by torrential downpour so we turned the pictures to the wall and five of us retreated under a convenient medieval bridge extension and talked about his cousin Barbara and why our demonstration was called ‘Good morning Mr Courbet’. His views about her work were close to mine. When we emerged from under the bridge we saw a wet cyclist on a lightweight bike. I was about to meet for the first time the publisher of a scurrilous journal.

Was the tiring day on the bridge worth the effort? And what had we learnt?

1. Paintings need to be small enough to fit into bin liners and have robust frames. It is best to have a number of solid frames in three sizes. Uniformity makes the exhibition look more professional.

2. John, our market frame-maker, showed that by using handwrap (a sort of clear film) on a handle you protect the frames, have something to attach titles to, but more important you could attach painting and display boards to bollards and railings.

3. You need someone close at hand with a car big enough to carry away the paintings.

4. Make sure that some of your pictures are explicit and targeted. If you’re hitting out at someone, have a hand-out which explains what you’re doing. The quality of the work is important. The majority must be able to sit happily in a public gallery. Avoid anything that is called ‘abstract’.

5. Take on big subjects such as Arts Council policy.

6. Don’t sloganise. Contrary to received wisdom people really enjoy reading a developed argument.

http://www.pontefractpress.com/

http://www.hepworthwakefield.org/

The Jackdaw Jul-Aug 2011