If any Jackdaw readers were still in doubt about just how rigged the contemporary art market is after numerous articles on the subject, many from the editor, then Phil Redman’s piece “The Crap Art Market” (The Jackdaw, no 108) should have put the matter beyond doubt. So I take all that as read. Less obvious is why the domination of that market by a cartel of a few large players means the only kind of art that benefits from their attentions will be crap. All art, from the least worthy, through to the mediocre and moderately good, and on to the truly excellent is capable of being hyped and having its value ramped up in a rigged market. It is by no means clear why such investors would only be interested in inflating the value of crap art.

If any Jackdaw readers were still in doubt about just how rigged the contemporary art market is after numerous articles on the subject, many from the editor, then Phil Redman’s piece “The Crap Art Market” (The Jackdaw, no 108) should have put the matter beyond doubt. So I take all that as read. Less obvious is why the domination of that market by a cartel of a few large players means the only kind of art that benefits from their attentions will be crap. All art, from the least worthy, through to the mediocre and moderately good, and on to the truly excellent is capable of being hyped and having its value ramped up in a rigged market. It is by no means clear why such investors would only be interested in inflating the value of crap art.

We need to look at the supply side of this market. If the contemporary art scene has more than its share of rubbish art, why are so many so-called artists supplying it? The obvious answer is easy money: the corrupted market, with its over-emphasis on novelty and sensationalism, has opened the doors to all kinds of chancers and charlatans who are simply seizing the opportunity to make a quick buck. I think this is too glib and the reality more complex.

Deep down in the psyche of every artist is the desire to create something valuable – not initially in monetary terms though this may later serve as confirmation of the achievement of this desire – but intrinsically valuable, and to create it, like the spider’s silken web, out of nothing but him or herself. Freud saw very early signs of artistic ambition in the over-evaluation that the infant playing with its faeces makes of its precious productions. It is a deeply narcissistic and omnipotent yearning and probably accounts for a certain unworldly and childlike quality that has become part of the artist stereotype. If however such ambitions remain at this level they are doomed, since to succeed artists must reach out to the world and draw inspiration from things other than themselves. Only in this way will they have something of value to reflect back to the world, which in the end will be the measure of their success. (Tracey Emin with her almost entirely self-referential oeuvre must be living proof that this uncontroversial statement no longer applies at the lunatic top end of the contemporary art world). Yet the desire to be an alchemist, creating something highly treasured – be it art or gold – out of mere paints or base metals remains at the core of the artistic endeavour. And the same is true for writers and composers: mere words and notes replacing the painter’s pigments. Artist, writer and composer all soon learn that alchemy doesn’t happen by magic and that hard work, fine tuning of skills and an engagement with the world will all be necessary for colours to enthral, notes to sing and words to tell a story. But what happens if the market doesn’t demand art that enthrals? What if the market’s over-riding requirement is novelty and surprise and being different at all costs? If nobody is demanding excellence, there will be a race to the bottom in both senses of the word.

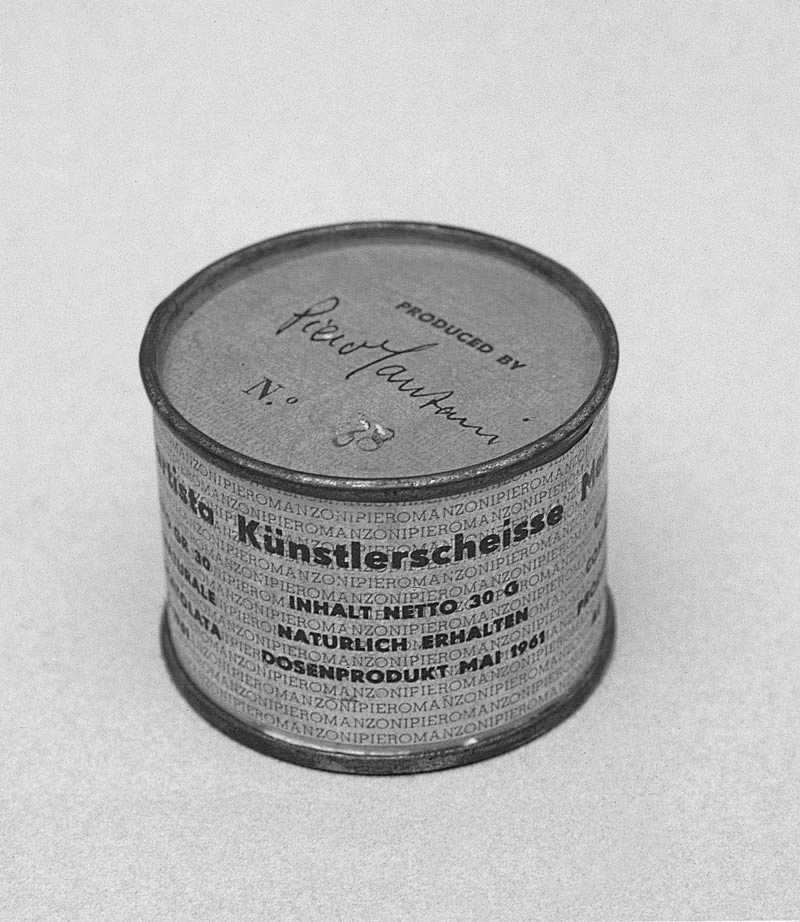

In 1961 the Italian artist Piero Manzoni famously exhibited a tin of his own faeces entitled Merda d’artista, translated on the tin in English lest the cadences of the Italian language left anyone in doubt about the bluntness of his intentions: Artist’s shit. He priced his faeces according to their equivalent weight in gold. Had he simply evacuated his bowels on a gallery floor he would almost certainly (in 1961 at least) have been thrown out as a mere exhibitionist and public nuisance. But by canning his shit he created just enough distance from the vulgarity of his conceit and, even more importantly, created an object which could be traded as a work of art. Untreated human ordure might have stumped even the most Duchampian of curators and dealers, but a can of shit, especially when produced in an edition of 90 – smart that, even with its weight in gold, one motion would hardly have made Manzoni wealthy – gave the critics plenty else to write about other than whether shit can really be art. Otherwise, back then at least, the answer might just have been a resounding “No”. On the other hand, mass production, irony, contextualization, valuation, the gold standard, alchemy and so forth all became legitimate talking points which could imbue the cans and their contents with artistic significance. Yet the original impulse behind the “work” remains the same: Manzoni was challenging the world to accept his excrement as a work of art, the very thing which Freud suggested lay at the root of many artists’ earliest motivations to pursue a career in art. Freud would have enjoyed too the Oedipal overlaying to this story. Manzoni claimed that what had prompted him to create the piece was his father’s taunt that his work was shit. Recently one of Manzoni’s tins sold at Sotheby’s for £97,250, seventy times its weight in gold. They have become collectors’ items and are held by many national museums, including the Tate (which bought its tin for £22,300 in 2002).

One has to hand it to Manzoni. With one simple gesture he became a far more renowned artist than before, made himself well off, and by that success produced a strong rebuttal of his father’s insult. But crucially it was a gesture. To some a witty and succinct gesture, to others an infantile one, but a gesture none the less. If it is deemed a clever and profound enough gesture to be regarded as a work of art, then its status as an artwork has more in common with a performance piece, a stunt or a comic sketch. The context is all. A can of shit unmitigated by some action can only ever be shit. Placing it in a gallery and linking its price to its equivalent weight in gold is the meaningful, possibly artistic element. This action, this gesture is no more and it should be stressed no less a work of art than many stunts or comic sketches which leave no marketable art object behind. It is also less a piece of visual art than a comic sketch because one does not have to have seen either what Manzoni did, or the can of shit itself, to “get it”. The art work, if we concede it to be one, is a purely conceptual work, entirely dependent on the profundity of the artist’s gesture for any evaluation of its merit. A blind person could equally appreciate the wit and significance of Merda d’artista as a sighted person. Since the art lies in the gesture, the can of shit itself is not the art work but merely a relic or prop reminding us of it. To treat it as otherwise, to exhibit it in a museum for people to look at as an artwork and to value it at many times its weight in gold is to collude with a kind of fetishism.

We may be fascinated by the original scores of Mozart or Beethoven’s music but we go to a concert to hear what they wrote because their art resides in sound. Looking at the original manuscripts does not, any more than looking at a newly printed copy of the score, give us that experience. The manuscripts, like Manzoni’s cans, are art relics albeit of much greater artistic achievements. We go to a museum to look at a great modern masterpiece like Picasso’s Guernica because only by looking at it have we any chance of “getting it”. But a conceptual work that functions on the level of a gesture can be fully appreciated (or despised) without being seen at all. To exhibit the ghost of that gesture in a museum alongside artworks that are truly visual experiences is to confuse two entirely different animals. Giving them equal status as works of art is to further confuse the public, already largely persuaded that art can be anything that an artist chooses to call art. The tautologous absurdity of this idea ought to be enough to prevent its rise and rise, but it continues to make headway and is close to becoming accepted by vast swathes of the populous. Grayson Perry’s Reith lectures, well received by Radio 4 listeners it would seem, takes this nonsense as a given. Saying that art is anything an artist calls art simply shifts the problem of definition on to what is an artist. Since an artist is someone who makes art (but art can be anything the artist says it is), we’re no further on. We arrive at the nonsense of everything being art and everyone an artist, at which point both words become quite meaningless.

I’m not arguing that a good case cannot be made for regarding what Manzoni did as art. It strikes me as being a wittier and cleverer piece of conceptual art than many. My point is that the art happened in 1961 and the can of shit is but a relic of that event, and relics should not be confused with living art works. A great Rembrandt self portrait is as potent today as the day it was painted. It isn’t the relic of an idea Rembrandt had three and a half centuries ago. It is that idea, an entirely visual one, and one that can only be appreciated by looking at it. Whereas the exact appearance of Manzoni’s can matters hardly one jot to the strength or weakness of his idea. Yet it is in the interests of the market, and the artist, to fetishize the object in order to make money out of it. In this sense it is a con and its artistic status spurious.

The same applies to Duchamp’s bog-standard mass produced urinal. If there was art involved, it was in what Duchamp did with it. The art, if any, lay in the audacity of Duchamp’s submitting it for an art exhibition, turning it upside down, calling it Fountain and signing it R. Mutt. If this series of actions are felt by enough people to be profound, thought provoking and witty enough, then for them at least Duchamp’s stunt is a piece of art. The urinal remains just that: a urinal. It cannot itself be magically turned into an art work because an artist points at it and says it is. This is omnipotent and magical thinking of the most primitive kind.

It is rather remarkable how much conceptual art, and likewise its fore-runner “found art”, as well as much other contemporary art, mirrors the alchemist’s dream of magically turning the basest of materials into gold. Often, as with Manzoni, this involves crap itself. Many others reference faeces and urine more obliquely. Since Duchamps urinal we’ve had Warhol’s “Oxidization Series” (involving urination), Gilbert and George’s “Naked Shit Paintings”, Helen Chadwick’s “Piss Flowers”, Andrea’s Serrano’s “Piss Christ”, Paul McCarthy’s “Shit Face Painting”, Chris Ofili’s use of elephant dung and Martin Creed’s “Body Docs” – videos of people defecating and vomiting – to name but a very few. Fortunately we have been spared Damien Hirst’s plan to cast an enormous turd in bronze, (why not gold, Damien?). But may be we’ve still got it coming to us. Even more common is the use of rubbish to make art, giving rise to a whole genre of art known as trash or junk art. A great many other contemporary artworks include rubbish or detritus. Tracey Emin’s unmade bed with its used tissues, condoms and discarded underwear is a good example as well as being a classic case of “it’s art because I say it is and I’m an artist”. We’ve moved from the realm of the nursery and any special pleading for the value of poo-poo, to that of adolescence. A cartoon at the time had an exasperated parent yelling at his teenage daughter and her unmade bed “I don’t care if it’s art, make it!” Which goes right to the point: Emin wants us to accept her messy adolescent life (represented by her bed) as art without her having to make anything.

As with Manzoni’s Merda d’artista the use of faeces or rubbish does not preclude a work from being art. This must in the end depend on the skill with which such materials are employed and the depth of feeling and intellectual rigour that informs the finished art work. What I am suggesting is that the unconscious motivation that underlies the artist’s preference for such materials with their potential to generate quick publicity, as well as the penchant for found objects or “ready mades” is likely to be a wish to magically transform shit into art. The clues are in the puerile feebleness of so many of the ideas behind such art and the childish need for instant attention they so often betray. If Freud was right that at the deepest level of motivation artists were once infants playing with their poo and imagining it to be precious, none of this should surprise us. If the art market colludes with these primitive omnipotent fantasies by overvaluing infantile impulses and stunts, artists will surely supply it with crap.

Patrick Cullen

The Jackdaw, 2014