Few save masochists would venture as far as Kendal in order to see work by Bethan Huws, not least because unless you happen to have attended one of State Art’s indoctrination sessions you won’t have heard of her. A taste considered acquirable only by the starving, Huws is among State Art’s chosen apostles. Sadly, she is unmissable in Kendal for the wrong reasons.

For most the Lancashire town is distant and in previous decades only the likes of George Romney, who was born there, Sheila Fell, a landscape painter now forgotten but at her best worth travelling to see, and Thomas Bewick, father of English wood engravers, have attracted this paper to its fastness. All were worth the trip. Additionally, several decades ago the town’s Brewery Art Centre staged ambitious photography exhibitions, but no longer.

For most the Lancashire town is distant and in previous decades only the likes of George Romney, who was born there, Sheila Fell, a landscape painter now forgotten but at her best worth travelling to see, and Thomas Bewick, father of English wood engravers, have attracted this paper to its fastness. All were worth the trip. Additionally, several decades ago the town’s Brewery Art Centre staged ambitious photography exhibitions, but no longer.

The main event at Abbott Hall until September 15th is landscapes by Graham Sutherland, an artist once considered among the country’s finest artists but now relegated to the long list of those dismissed and, like Trotsky, as good as doctored from the record. Like his contemporary, the equally disregarded John Piper, Sutherland is considered the sort of parochial petit maître in which British art specialised during the mid-20th century.

Until recently, of the Tate’s 56 works by Sutherland none was on display although three pieces have been dusted down for the Millbank rehang. Between 1935 and 1945 Sutherland was among the six most recognized artists working in Britain, each of whom was aware of what the other high flyers were up to. With knowledge of the latest Parisian isms, and especially Surrealism (this undoubtedly due to the well-promoted London surveys of this movement in the mid-30s), Sutherland explored form well beyond the conservatism of his instinct and training.

This is an absorbing exhibition organized by those understanding of and sympathetic towards Sutherland’s direction. Among a small number of important works are pieces showing the inventions needed to arrive at an appearance, a feel, beyond the superficial and well distant from the topographical. Exaggerating natural forms which attracted him, his work is the equivalent to the experience of a country walk during which details and oddities are noted and accumulated. Like Piper, he found no idiosyncracy of natural shape uninteresting.

The perfect accompaniment to the first room of the exhibition which traces Sutherland’s beginnings in detailed pastoral etchings inspired by Samuel Palmer’s bucolic prints (some are helpfully included), would be silence. Just as you need to listen to a landscape by Rubens or Constable an ear helps with these scenes too.

Unfortunately, that possibility is ruined by noise from a Bethan Huws’s video installation. Called Singing for the Sea, and made in 1993, Bulgarian grandmothers wearing traditional costume stand wailing in a circle on a beach. Officially their singing is called ‘antiphonal’ whilst, unofficially, it is a bloody awful racket. (The piece was commissioned by Artangel and is on loan from the Tate – who doubtless, between them, also supplied the ‘masterpiece’ tag with which this pretentious guff is accompanied.) The grannies were flown to Northumberland to do their performance. Doubtless there was a very challenging and cutting-edge reason why this noise couldn’t have been recorded more cheaply on the Black Sea coast. The women moan and shout incessantly, loudly, near the tops of their voice. As an exercise in fatuity [I think you must mean ‘deeply spiritual ritual’? Ed] this takes some beating.

The upshot is that because of these bellyaching peasants concentration on Sutherland is impossible. The few paying visitors present at the same time as The Jackdaw were all of a mind that this was an outrageous intrusion tantamount to deliberate sabotage. The price of having Huws’s ghastly piece in the gallery, inevitably described by the fools responsible for installing it as ‘unique’ and ‘haunting’, is the impaired appreciation of everything else. Can those who promote this species of material be so unaware that looking at pictures requires undistracted attention? Perhaps their experience originates solely in a period when painting was so unfashionable that they never mastered the art of looking at it properly. Some people now working in galleries don’t seem to understand that noise is a distraction which flies in the face of why a gallery should exist in the first place. There must be a venue somewhere appropriate to antiphoning Slavs but it isn’t anywhere close to a landscape painting.

A few issues ago The Jackdaw noticed an exhibition of John Piper’s landscapes at Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester. In the decade after 1935 Piper, as was illustrated there, and Sutherland were aware on one another’s experiments, and their drawings exhibit a related sympathy. Their landscape pictures, the one working in Snowdonia, the other in Pembrokeshire, converse and compare notes. In both, for example, drama and threat are emphasised by daylight scenes appearing to take place in darkness. Though their aims and methods couldn’t be more different, the results are close in effect.

In passing, it is fashionable these days to compare Sutherland unfavourably with Bacon on the grounds that the latter was more original. This exhibition, featuring works well in advance of Bacon’s post-war debut, gives the lie to that exaggeration. Bacon was well aware of Sutherland’s stylistic experiments to get beyond appearances and narrative logic.

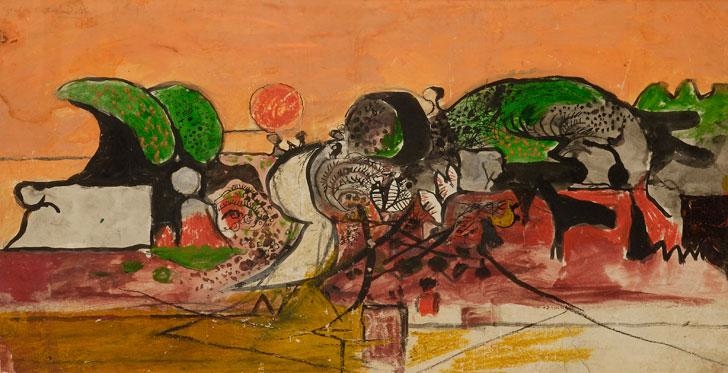

What is impressively illustrated in these pictures is the deliberate, intelligent progress they chart towards a way of depicting landscape so it is simultaneously recognisable and mysterious and its substance both solid and dissolving. In a work such as Rock Form in a Landscape (opposite) the style parallels closely what Piper was simultaneously attempting in Nant Ffrancon. In another work here (above), a commission for his war artist duty of depicting those working in mines, Sutherland’s knowledge of Moore’s drawings (particularly in the technique of using contour lines to emphasise solid volume) is apparent in the figures. It would seem that the more exploratory artists of this moment were working fully aware of one another’s advances while not being party to any movement.

The exhibition is a reminder of Sutherland’s status as an explorer at a time when his reputation could scarcely be lower. The show could bear having more works in it. Looking through the 55 Sutherlands owned by the Tate and which are never on show, or ever likely to be, numerous other drawings (besides the three loaned to the exhibition) would have further amplified the journey Sutherland undertook during these years.

David Lee