The Tate recently named two new trustees, one of whom is painter Tomma Abts. She is a 44-year-old German, recently appointed Professor of Painting at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, who won the Turner Prize in 2006. As an artist trustee, she replaced Jeremy Deller, who won the Turner Prize in 2004. Abts’s paintings are all the same small size (48 x 38cms) – it is claimed this tic is conceptually crucial for a reason never convincingly explained – and consist of polite abstract designs which might have looked original on curtains at the 1954 Ideal Home Exhibition. So much for the Cutting Edge. The Tate claims her pictures “possess a formal definition and coherence that suggests that they could never have existed any other way … [and] seem to achieve what only painting can, inhabiting both this reality as an object or ‘thing’, and a parallel world with its own set of rules and relationships that demand to be judged on their own terms.” As per with their interpretive literature, all helpful stuff. Am I being cynical? Yes. Why? Because using any sensible criteria Abts doesn’t deserve to be a trustee of an important British museum.

The job of Tate trustees is to oversee the efficient running of the gallery “as guardians of the public interest” – and please note that it says ‘the public interest’ not ‘State Art’s interest’, for as you will discover these two mutually exclusive agendas tend to become blurred in the minds of certain individuals. Improbable as it sounds, guidelines for the functions of trustees are drawn up by the Tate itself, not by independent arbiters. Such complacency hardly reassures an outsider that the public interest, rather than the Tate’s, is being looked after. Indeed, such self-scrutiny is hardly better than the continuing disgrace of policemen investigating their own mistakes.

In 2008 the number of trustees was increased from 12 to 14 and as required by the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 “at least three” of these must be artists. Thirteen are appointed by the Prime Minister and the last is nominated by the trustees of the National Gallery from among their own membership. Unlike their fellow trustees, who are mainly those with business expertise, and who can serve up to two terms of four years (a period of office trimmed recently from five), artist trustees currently serve only one term of four years. You may find it odd – I certainly do – that while there are three contemporary artists with gilt-edged State Art credentials on the Tate’s board of trustees there is no place for a single art historian. I’m obviously old-fashioned because a museum of historical art with no art historians sitting on its governing board seems verging on the perverse.

When an artist trusteeship becomes vacant it is widely advertised in the papers, giving the impression that any capable, knowledgeable, articulate artist of repute might apply. Nothing could be further from the truth, for there is a codicil written in invisible ink along the bottom of these ads, which reads: “If you have not won or at the very least been nominated for the Turner Prize, kindly fuck off and don’t waste our time.” The Tate squanders scarce cash paying for these advertisements which are nothing short of a calculated deception. Artist trustees are in fact a self-appointed clique comprising only winners of the Turner Prize with a couple of reliable also-rans chucked in. Since new regulations were imposed in 1992 the only exceptions to this rule have been Julian Opie, who famously refused his nomination for the Turner on the grounds that the prize “had become a frivolous publicity stunt”, and Bob and Roberta Smith, the sobriquet of a dimwit called Patrick Brill, who is otherwise a regular purveyor of infantile stunts at Millbank – you may recall his Tate Christmas tree whose lights visitors were asked to illuminate by peddling a generator. He’s very concerned about the environment apparently.

Being a trustee involves attending six meetings a year and is said to require a day a month in reading and preparation. I must point out that the Tate’s artist trustees are easily the worst attenders at these meetings, and are frequently absent. In the case of Anish Kapoor (Turner Prize winner, 1991) his absenteeism, which included missing half the meetings in two consecutive years and scarpering early from others, would have surely seen him sacked from the board of any efficiently run private enterprise.

Of currently serving artist trustees two are Germans – besides Abts the other is magazine photographer Wolfgang Tillmans (Turner Prize winner, 2000). Could they really not find a British photographer, or even a British abstract painter, worthy of these positions? Admittedly, Germans do most things better than we do but surely this is insulting to British artists. And how can a professor at a German art school, which presumably requires her to actually attend some of the week, perform the duties of a trustee required to be resident here?

The process by which artist trustees are selected – laughably characterised as “an open competition” or “an open competitive process” – is indicative of what happens when a clique achieves a complacent monopoly and is allowed by servile arts commentators to get away with it. Minutes of meetings make it clear that artist trustees are encouraged to invite applications from those they consider suitable as their own replacements, especially when candidates who have responded to the ads are not considered worthy, which one may reasonably surmise is always. Indeed, I wonder if there was ever a case of a successful artist trustee having responded to the ads rather than having been – that weasel word – ‘invited’ to apply… And so Turner Prize winners beget other Turner Prize winners, or at the very least other near-misses of that persuasion.

Candidates for artist trusteeships are interviewed by a panel comprising trustees, including the artists, plus an “independent assessor” who is present to ensure that legal niceties, “best practice” etc., are observed and everything looks above board. But how can it be above board when only Turner Prize winners are appointed? Perhaps this independent assessor ought to be involved from the start of the process in order that more than Turner Prize nominees might be seriously considered, if for no other reason than to keep up appearances of openness. Eyebrows would be raised at such a narrowness of potential candidates in any other sphere of public life: imagine, for example, the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces always being selected from the same regiment.

You may ask why is it so important for the convenient running of the Tate that its artist trustees are always winners of the Turner Prize. The answer is for the obvious reason that having been awarded a career-changing gong by the institution of which they are now overseers, they will never rock the boat by asking too many tricky questions about the Tate’s direction in its dealings with contemporary art. This is one of many ways by which State Art has become institutionalised: no one but the reliably subservient is ever allowed on the inside to question Tate, or indeed Arts Council, policies.

On the other hand these parti pris trustees can be useful when outside criticism of the Tate becomes noisy. For example, in July 2004 Trustees discussed newspaper coverage of a Tate work, Rodin’s The Kiss, which Cornelia Parker (who was nominated for the Turner in 1997, the year it was won by Gillian Wearing, inevitably herself a recent artist trustee), had the previous year controversially wrapped up with a mile of string. This stunt was claimed by the artist to be “challenging the claustrophobic nature of relationships”. Artist trustees present in the meeting (which included the aforementioned Wearing) were able to defend their fellow artist for the benefit of other sceptical trustees. They pointed out that it was the job of the Tate to provoke controversy and discussion, which this work did.

It is in the interests of these artist trustees to support the Director. They know they will be serving only for a brief period following which they might reasonably look forward to the reward of a Tate retrospective or other continued patronage, purchases etc.

Serota has stated a preference for such younger trustees. Referring to the trusteeship of Anthony Caro many years before, he remarked in 1998 to the Sunday Times: “Tony was well over 60 when he became a trustee. He was a very effective trustee, actually. He cared passionately about certain things and was a powerful force … but it just seems to work better when you have artists who are a new generation, or indeed erring on the younger side, really.” And we know why he thinks it “seems to work better”, because older artists of a more independent, more knowledgeable, more experienced character might argue cogently for a policy or direction other than the one being pursued by the Director. They have nothing to lose by disagreeing with him. Let’s face it, the current crop of artist trustees is in Serota’s pocket. They owe him and he knows it. He can rely on their support without a second thought.

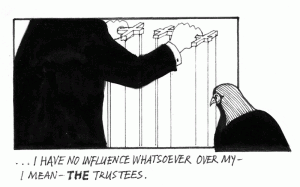

In a 2008 interview Serota said of his trustees: “I don’t have any part to play in their appointment”. Remember this, it’s important and we’ll return to it in a second.

Many years ago Serota said that public nominations for the Turner Prize (perhaps you don’t remember that ridiculous charade whereby we all wasted our stamps and faxes) were seriously considered by the judges. We discovered in 2006 what we already knew, courtesy of an indiscreet Turner Prize judge, that this was in fact a lie and they were binned with risible disregard. We also discovered at the same time, and from the same source, that Turner Prize judges were given a list of appropriate artists and exhibitions – just to help them along you know, point them in the right direction. And there we were thinking in the innocence of our ignorance that they might nominate anyone…

Serota also stated in 2005 that the Tate only rarely acquired work by serving trustees. The Jackdaw checked up on that and discovered (see the editorial for Dec/Jan 2006 on our website) that he wasn’t telling the truth. Indeed, this whopper cost him a bollocking from the Charity Commission. There were also a number of other flagrant economies with the truth concerning the Tate’s acquisition of work by serving trustee Chris Ofili, who was naturally a Turner Prize winner (1998), which also resulted in another six of the best from the CC. (I almost mentioned here the fact that in the last editorial – also on our website – we indicated how the Tate recently misled us over their attendance figures, but you must be getting fed up with that one.)

So, bearing in mind Serota’s far from perfect form, when he remarks “I don’t have any part to play in their appointment” I need to ask myself: ‘Do I give him the benefit of the doubt and believe him this time?’ Well, as it happens, no I don’t. Even cursory familiarity with the Trustees’ minutes betrays this one as untrue. On the contrary he is frequently involved in their appointment; indeed, the process of Trustee appointment is administered by his own office. He even attends candidate interviews “in an advisory capacity”. Presumably he offers ‘advice’ which plays no material part in the process, so why is he there in the first place? Indeed, we read on: “The key stages of the appointment are overseen by a panel which will normally include the Director.” (Who, presumably, doesn’t play any part.) On one recent occasion he encourages artist trustees to nominate likely candidates for their replacement knowing only too well the sort of artists they are likely to suggest. No part?

Let’s have this one straight: Serota is ‘advising’ on the appointment of someone, a trustee, who will function as his own employer. This is a wretched abuse of the supposed ‘independence’ of process and would be considered as much in any other public body. It is, as usual, as blatant a conflict of interest (not to mention a betrayal of ‘the public interest’ about which the process purports to be so concerned) as you would expect to find at the Tate, whose management of conflicts of interest, incidentally, was declared woefully inadequate by none other than the Charities Commission.

The Tate should not be involved with either the compiling of its own trustees’ duties, or in the nomination or selection of Trustees themselves. How can ‘the public interest’ be considered served when the organisation under scrutiny is writing the job description of its own scrutineers. If we are to have artist trustees let’s have them from a cross-section of the artist community and not just those representing the Turner Prize. And let’s have some eminent art historians in there too.

David Lee

The Jackdaw May-Jun 2011