American painter Christopher Wool (b. 1955) has been described by the New Yorker as “perhaps the most important painter of his generation”. Christie’s are in less doubt, describing him as “one of the last century’s most influential artists”. Even by the risible standards of bullshit spouted by auction houses and art dealers this is ridiculous. I’ve never heard anyone, artist or otherwise, ever say they were influenced by Wool. Have you? Well have you? Indeed, I’d never heard of him at all until about a year ago.

American painter Christopher Wool (b. 1955) has been described by the New Yorker as “perhaps the most important painter of his generation”. Christie’s are in less doubt, describing him as “one of the last century’s most influential artists”. Even by the risible standards of bullshit spouted by auction houses and art dealers this is ridiculous. I’ve never heard anyone, artist or otherwise, ever say they were influenced by Wool. Have you? Well have you? Indeed, I’d never heard of him at all until about a year ago.

Wool joined Gagosian in 2006, since when the noughts increased and the words got longer. In 2009, courtesy of an organisation called The American Fund for the Tate Gallery, the first of two Wools entered our national collection – the second, acquired in 2012, was also secured in part courtesy of this same influential body. No institution in the UK has ever staged an exhibition of Wool’s work, but let’s face it such a ‘celebration’ can’t now be far off. His backers will surely procure one soon. I wonder which gallery will be first to follow the money.

To investigate how the art market operates I’ll concentrate on the sale of one of his pictures for two irreconcilable reasons: first, like Polaris blasting from under the ice cap, his reputation has been suddenly, suspiciously meteoric; second, I can’t discover an atom of merit or originality in anything he does. He is, therefore, a revealing example of how the art market, which is so disproportionately influential in dictating what we see in public galleries, is run for the investment benefit of rich people. (One of the most important dealers in contemporary art said recently of his collectors: “They have no interest whatsoever in art; they look at paintings as a diversification of their investments.”)

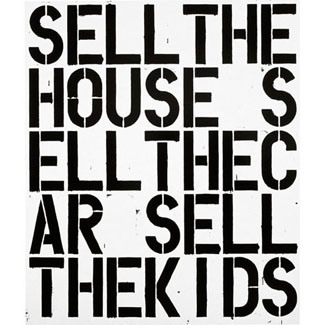

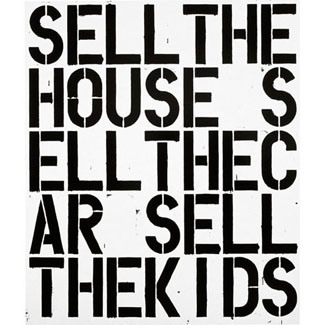

Illustrated opposite is Apocalypse Now. This 1988, 7’ x 6’ work, painted in polyester enamel on aluminium, was sold by Christie’s last year for $26.4 million, over three times the previous artist’s record. Manifesting more than a trace of evangelical fervour, the person who bought it gushed: “I wanted the absolute best work by that artist and this is the best of the best. It’s in another league. There is Apocalypse Now and then everything else.” Why it should be ‘better’ and more valuable than similarly fabricated Wools reading SEX LUV, FOOL, BAD DOG and IF YOU CANT TAKE A JOKE YOU CAN GET THE FUCK OUT, one can only speculate.

The technique is stencil, in mimicry of the graffiti legends and adverts which are supposedly its inspiration. And before you commend the concise nihilism of the message, these words are not the artist’s own. They are the looney Kurtz’s exhortation to his abandoned wife in Coppola’s Apocalypse Now: “Sell the house. Sell the car. Sell the kids. Find someone else. Forget it. I’m never coming back. Forget it.”

Nothing about this piece, either in its handling or conception, might make you think it is of remarkable value. Indeed, objectively there is no good reason why it might not be worth 25 bob instead of 25 million. What establishes its value is something you can neither see nor understand without being indoctrinated as to what it is … usually by someone with an interest in flogging it for as much as possible. Its value resides purely in its perceived status as a tradeable luxury. It has, curiously, no more intrinsic value than any other share certificate.

In its short life Apocalypse Now has passed through ten billionaire collectors. All were Americans except one, Frenchman François Pinault, five back, who is the proprietor of Christie’s, the firm who sold it this time. Incidentally, the owner before Pinault was Donald Bryant, until recently a trustee of MoMA New York who is also on the aforementioned ‘American Fund’ committee of the Tate, which was instrumental in the Gallery acquiring both its Wools. Californian winemaker Bryant obviously likes Wool, but not sufficiently, it seems, to hang on to what is allegedly his pièce de résistance. You will have noticed that the world of posh art is a very small and incestuous one.

The speed of turnover in Apocalypse Now – 30 months on average – tells us something about the motivation of modern collectors, for whom genuine discernment would appear to be the last thing on their mind. The very idea of connoisseurship or discernment in collecting contemporary art is an absurd notion when the relative value of a work can be made up so it flies in the face of the little you can actually see. Art is now a fund manager’s hobby, a gamble or a pitch from which, as with any other investment, profit is periodically milked.

The last seller of the picture, hedge-funder David Ganek, is also a trustee of the Guggenheim Museum in New York where Wool just happened to be enjoying a retrospective coincident with the auction of Apocalypse Now. In 2010, Ganek’s business partner was convicted for insider trading. Though himself deemed a co-conspirator Ganek was never charged. He left his company and paid $25 million in fines. There is a book to be written about the connection between contemporary art and insider trading. Everyone has now forgotten that the first sponsor of the Turner Prize, Michael Milken, the inventor of junk bonds, got four years for related offences. No more telling indictment of the contemporary art market exists than that it appeals to high-risk investors, hedgers and generally shifty operators to whose activities the cachet of art ownership is used to lend a patination of social respectability.

Was the sale of Apocalypse Now a straightforward auction? No it wasn’t. It was sold before the sale because a guarantor had underwritten the low estimate price of $15 million. A third of the works in the same auction were also the subject of pre-sale guarantees.

Christie’s threw their all behind this lot claiming that Apocalypse Now “is the emblem of a generation” – an obvious lie. They continued: “Christopher Wool’s Apocalypse Now is the essential image of our times… It’s much anticipated appearance at auction, firmly places Wool amongst the pantheon of great masters of the 20th century.” There you have it: “the essential image of our times”. Not the twin towers, or Obama being sworn in, or Neil Armstrong, or Mandela striding victorious from jail, or tanks in Prague or Tianenmen Square, or even Sergio Aguero scoring in extra time, but this second-hand slogan.

And what of the artist himself? He has said: “With the painting the inspiration comes from the process of the work itself. Like music making the work is an emotional experience. It’s a visual language and it’s almost impossible to put words to it.” Not half.

What conclusions might we draw from all this perversion of genuine standards:

1. Monetary value is unrelated to aesthetic worth. By looking at contemporary art you can’t even guess to within three noughts what it might cost.

2. Once a powerful cocktail of mutually interested dealers and speculators get behind an artist their rise is unstoppable. The auction market in contemporary art is a game played by six of the world’s biggest dealers, two salesrooms, 40 artists, about 30 billionaires and a clique of subservient museum directors and careerist curator-clones. No one else matters. In 2012 11 of the top 20 artists sold at auction were represented by Wool’s dealer Gagosian.

3. Most commentary on the art market is disgraceful advertisement.

4. At the top end, the art market encourages a sort of religious cult participation by hobbyist fat cats eager to cash in on safe bets.

5. When the auction market has nothing to do with liking art or actual visible qualities, the dealer is happy, the artist is happy, the seller is happy, the other collectors of the same artists’ works are happy, and the auctioneer is deliriously, pants-wetting happy.

6. The cowardly complicity of State Art before this squalid system is a shocking betrayal of what they really ought to be standing up for.

The whole thing is a filthy racket.

David Lee

The Jackdaw, Nov-Dec 2014