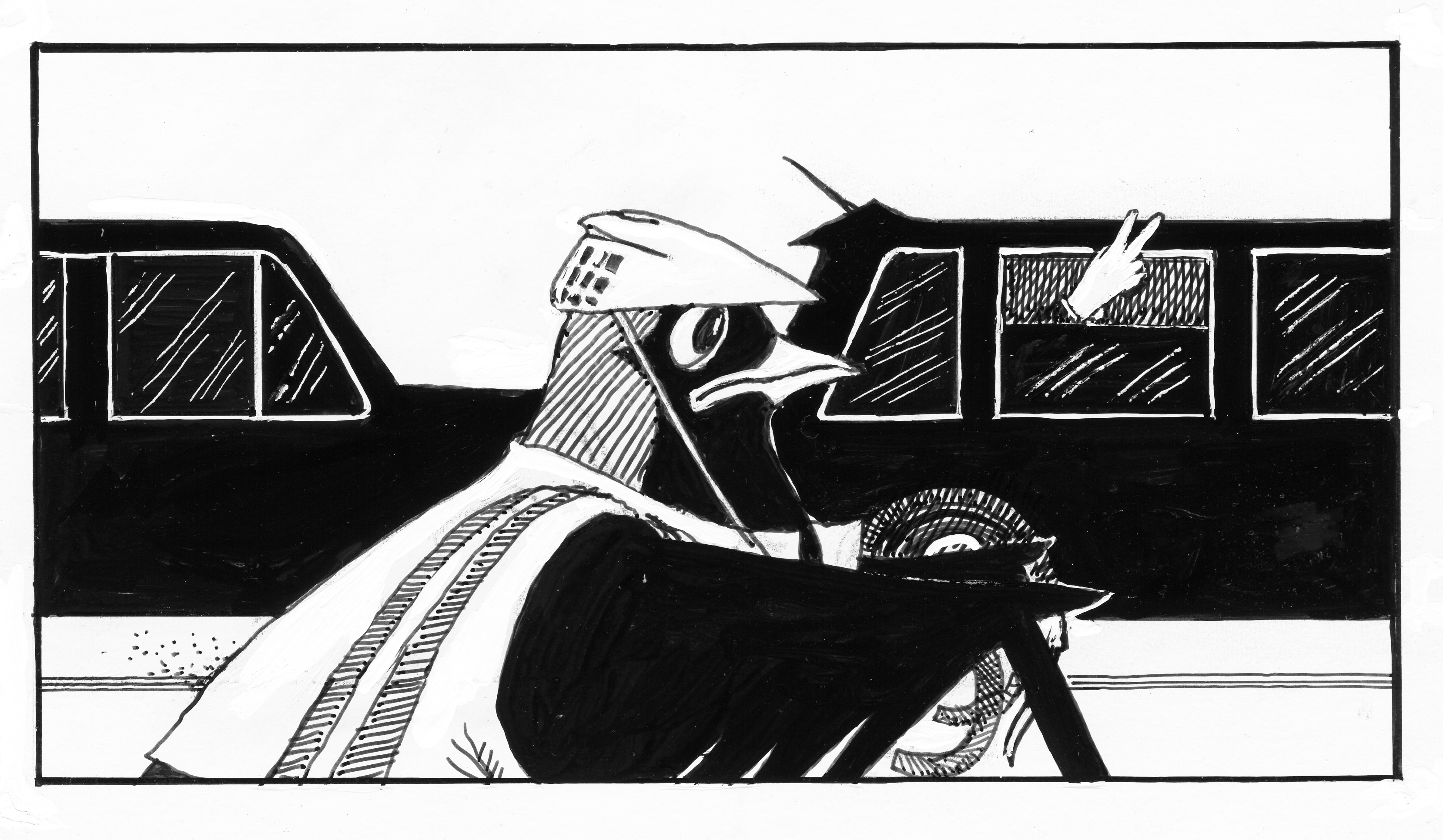

The last three editorials have dealt with a charity called the Serpentine Gallery. We’ve observed limousines lined up outside signifying whose interests the gallery really serves. We have identified overmanning and fat cat pay increases for two directors. And, last time, we highlighted an outside PR agency working between press and gallery in order to disarm justified criticism.

Apologies for boring you further, but there’s more. I’m not satisfied we’ve got to the bottom of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s presence at the Serpentine. He is, after all, a second highly overpaid director in a publicly funded gallery whose peer organisations employ only one director for a quarter of the cost of Obrist and Peyton-Jones combined. I question the need for the supernumerary Obrist.

Apologies for boring you further, but there’s more. I’m not satisfied we’ve got to the bottom of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s presence at the Serpentine. He is, after all, a second highly overpaid director in a publicly funded gallery whose peer organisations employ only one director for a quarter of the cost of Obrist and Peyton-Jones combined. I question the need for the supernumerary Obrist.

When I asked the gallery how many days Obrist spent there in 2013 they answered, ambiguously to my mind: “He works full-time at the Serpentine gallery.” Well, yes. But hang on a minute: “He travels a great deal, usually at the weekends, and works remotely at these times.” Why does organising an exhibition programme for the Serpentine involve such “a great deal” of travel?

You may recall from a recent editorial that Obrist enjoyed an almost 50% pay increase to between £130,000 and £140,000 a year, putting him on a par with major museum directors worldwide. For example, he earns considerably more than the director of Tate Britain who is responsible for a gallery many times larger and immeasurably more significant than the Serpentine, not least because it has responsibility for the most important collection of British art.

The long inventory of ‘foreigners’ Obrist has done during his eight years at the gallery suggests the Serpentine plays at best second fiddle. He has recently curated exhibitions in Essen, Berlin, Zurich and Sao Paolo and published books about Chinese Art, Ai Weiwei, several volumes of interviews and the self-aggrandising The Art of Curation (Allen Lane) published this March. Hot on the heels of this lot, he will co-curate the Swiss pavilion at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale along with the architects of Tate Modern. In the two most prominent announcements of Obrist’s new job nowhere was it stated that he is co-director of the Serpentine Gallery – as though this is just another sideline.

This spring he is also curating Luma Arles, a huge enterprise lasting seven months; but this is nothing unusual because he appears to have done it every year since 2008. The Luma Foundation, to which Obrist seems closely attached – both are based in Zurich – also supports the Serpentine. (Luma was founded by Maja Hoffman, a pharmaceuticals heiress, who also serves as a trustee of the Tate, whose film programme, among other things, she pays for.) If Obrist can curate all these major events at the weekend how come it takes him so much time to curate so few exhibitions at the Serpentine? It defies belief that Obrist is anywhere near full time in London. He can’t be. So why is he earning twice the going rate even for a full-timer?

Could it be that what many of us have suspected for years is true; that there isn’t actually that much involved in curating. It’s just a fancy title signifying not much more than blethering in tongues, writing atrociously and poncing about in black trying to look intelligent.

The latest accounts for the Serpentine have been posted. They show that since last year the two directors have had their pay cut back (to £120,000 and £110,000 respectively) but nevertheless to a level which still constitutes a 33% and 37% pay increase in two years. Additionally the Serpentine now has three people earning more than the director of Tate Britain and while the Tate, with its vast and complex organisation and collections, has only three staff earning over £100,000, the Serpentine has two.

The Serpentine Gallery has become a gravy train and if the Arts Council had any balls it would investigate immediately whether its £1.3 million a year subsidy is money well spent.

David Lee